I recently made bigos, a hearty Polish stew, using the recipe I got from my friend’s mother. I’ve loved bigos ever since I first had it at her house, back when I was studying abroad. The recipe has three ingredients: sauerkraut, ham hocks, and dried mushrooms. But bigos is a kind of kitchen-sink dish; you can add whatever you’ve got wilting in the fridge that you need to use up. Bigos really hits the spot for me, especially on cold winter days. But I wouldn’t call it pretty.

I recently made bigos, a hearty Polish stew, using the recipe I got from my friend’s mother. I’ve loved bigos ever since I first had it at her house, back when I was studying abroad. The recipe has three ingredients: sauerkraut, ham hocks, and dried mushrooms. But bigos is a kind of kitchen-sink dish; you can add whatever you’ve got wilting in the fridge that you need to use up. Bigos really hits the spot for me, especially on cold winter days. But I wouldn’t call it pretty.

As the bigos was cooking, I texted Sukrit. We talk about food a lot. He’d never heard of bigos. “My mouth is watering just looking at the recipe on Bon Appetit,” he said. Out of curiosity, I pulled up their recipe. Their photo looked nothing like my bigos, nor like any bigos I’d ever seen.

This got me thinking about photos of food. It’s beyond cliché that people of a certain age are wont to take photos of their food before eating it. (I wonder if there are more meals or selfies on Instagram.) We’re surrounded by photos and videos of beautiful food.

Nowadays we hear a lot about how social media is making us more insecure about our faces and bodies. But what about our food? What is it doing to me to see, day after day, that so-and-so is always eating meals apparently plated by a Japanese Zen-master-cum-chef? And that this same chef works for all my friends?

I recently heard an interview on the Guardian Books podcast with Josh Cohen, whose book Not Working was just released. As an aside in the conversation, he mentioned this phenomenon of seeing amazing pictures of food on Instagram. He doesn’t like these pictures, he said, and he finds the phenomenon troubling. We can’t feel the texture or inhabit the lived quality of that food, thus digitized. All we can do is fetishize it and click the heart button.

Years back, there was plenty of hubbub about the photo-manipulation techniques that McDonald’s et alia use to nip-tuck their food for advertising. I haven’t heard anything about this for the past several years, but the gulf between the Big Mac on the ad and in real life is just as wide as ever. Maybe we’re not outraged about this anymore because we’re all doing it. Now, I don’t think (m)any of us are photoshopping our food pictures, but we certainly do think about angles, lighting and filters, all of which are stops on Photoshop Road. And, to be sure, there are apps for on-phone photo editing specific to food.

But even beyond photo-manipulation, restaurants seem to be paying more attention to their plating and presentation these days, what with services like Instagram and Yelp in the cultural fabric. You just never know which customer is going to post a picture. Maybe that’s a good thing. Beautiful food certainly adds to the experience. And if the food also tastes great, then why not? One of my most memorable dining experiences was at Studio in Copenhagen, where every plate that came my way was consummately Instagrammable. Yes, I even posted a photo collage. (Importantly, the food had the taste to back it up.)

View this post on Instagram

But we humble home cooks are feeling the pressure, too, in these days of social-media perfectionism. If we spend the time to make some tasty and beautiful food, we seem to feel the need to document it. We want the photos to exude all the things we’re feeling about the food, so we worry about the lighting and backgrounds and plating and all that.

I was with a friend once, and we were cooking an elaborate, multipart meal. If we’d planned better, perhaps everything would have been ready to serve at the same time. But as it was, it took a full hour between the first thing’s finishing and the last’s. Our plates looked wonderful in the photos. And don’t get me wrong: the food tasted fine. It’s just that everything was cold. We’re surrounded by these glorious pictures of food. And what sacrifices we make to contribute to furthering that glory—ad majorem cibi gloriam.

There’s a handful of cookbooks in my kitchen. They, too, are for the most part adorned with luscious photographs. When I peruse them, looking for a weekend project or something to cook for company, I even find myself skipping over the pages with no photos. Other times, the photos are intimidating. I might see a photo and think to myself, “That looks way too involved for me right now,” or, “I could never make it look like that,” which likewise makes me turn the page. It’s probably a familiar feeling. Like that pitiable and brave soul who tried to make Cookie Monster cupcakes, perhaps it makes you not want to try again.

There’s a handful of cookbooks in my kitchen. They, too, are for the most part adorned with luscious photographs. When I peruse them, looking for a weekend project or something to cook for company, I even find myself skipping over the pages with no photos. Other times, the photos are intimidating. I might see a photo and think to myself, “That looks way too involved for me right now,” or, “I could never make it look like that,” which likewise makes me turn the page. It’s probably a familiar feeling. Like that pitiable and brave soul who tried to make Cookie Monster cupcakes, perhaps it makes you not want to try again.

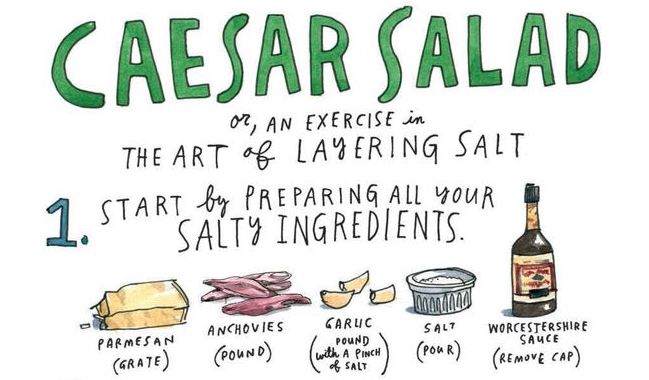

Last month I finally got the book Salt Fat Acid Heat, by Samin Nosrat, and immediately it struck me. There’s not a single photo in the book. But there’s plenty of imagery—illustrations, that is. They’re quirky, whimsical doodlings done by Wendy MacNaughton.

As you turn the pages, you’re met with drawing after drawing. Macerated red onions, dried beans in various states of rehydration, lifesize cuttings, hand-colored charts… There is something about the art in this book that is approachable and inspiring. Returning to Josh Cohen’s comment, illustration seems to show the lived quality of the food, even though it’s—by all appearances—much further from the food than is a photograph. Or is it?

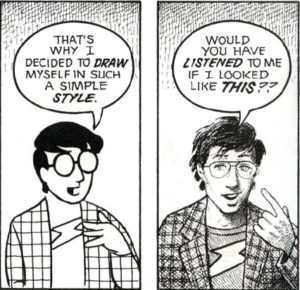

This reminds me of something in the book Understanding Comics, by Scott McCloud. Good comic book characters are visually ambiguous, he says, which allows the reader to insert themselves into the story. If there’s too much detail, the character comes across as defiantly other. We can’t identify with such characters. Perhaps pictures of food are similar: Too fanciful a photograph, and you can’t enter in; but with heart and ambiguity, you can.