Ah, the personal touch of a handwritten note.

Ever since the dawn of type, people have been talking about how special handwriting is. In type, the English alphabet has only 26 letters (make that 52, counting lowercase and capitalized forms), but in handwriting, there are infinite letters. Just think of all the ways you can write the letter g and have it still be recognizable. (Indeed there is an entire blog dedicated to this letterform.) When we read something handwritten, we get a sense of the personality and emotion of the writer. This is why, when printed Bibles came along, people found the words a bit lacking in spirit. And it’s why handwritten letters are so special for us, even today (if a bit sloppier).

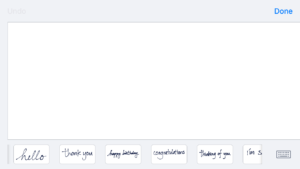

With digital technology, we’re no longer limited to keyboards and mice for input. With trackpads and touch screens, we can combine some of the personality of handwriting with the capability of electronics. The latest update to Apple’s iOS on the iPhone and iPad takes advantage of this, giving people the opportunity to send handwritten and drawn messages. Recipients can even replay the drawing to see how it came to be.

While exploring this feature, I was struck by what seems to be an absurdity: It comes loaded with a number of pre-written messages—hello, thank you, happy birthday, etc.—that you can simply tap and send. That is, you can send a handwritten message without actually having to write it. I guess I shouldn’t be surprised—it turns out ghostwriting love letters is a sustainable business (and I feel like it figured in the plot of a novel I read once, but I can’t remember what it was).

Still, this seems tremendously weird to me. Wouldn’t a recipient find it disingenuous to receive the exact same text again and again? Though, then again, will people actually use these pre-made messages? For now, all I can do is speculate.

What’s a book? We have a number of ways of answering that question. On one hand, a book is a physical object, a rectangular thing with pages held together with binding. My copy of Candide is a book. On the other hand, we also think of a book as the words that inhabit that object. When someone sees you reading Candide and says, “I’ve read that book,” they probably don’t mean they read the same copy you’re reading, but rather a different copy—perhaps from the library. So there’s a sense that all the different copies of Candide in the universe are somehow the same book. Nowadays, these copies aren’t all in print—we have

What’s a book? We have a number of ways of answering that question. On one hand, a book is a physical object, a rectangular thing with pages held together with binding. My copy of Candide is a book. On the other hand, we also think of a book as the words that inhabit that object. When someone sees you reading Candide and says, “I’ve read that book,” they probably don’t mean they read the same copy you’re reading, but rather a different copy—perhaps from the library. So there’s a sense that all the different copies of Candide in the universe are somehow the same book. Nowadays, these copies aren’t all in print—we have