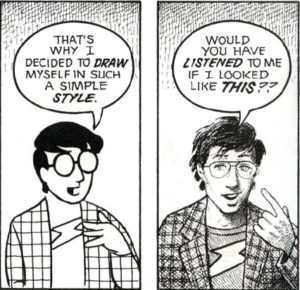

More and more my work is dealing with the philosophy of information (PI). A major figure in this area of philosophy is Luciano Floridi. His works are technical (i.e., difficult to read without a lot of training and patience), and we’re in need of some more accessible entries into his thought. To that end, here I’d like to mention just a few of the major concepts he brings up in his philosophy. If you’re interested in more, check out Betsy Martens’ “Illustrated Guide to the Infosphere,” as well as Floridi’s own works (perhaps start with The 4th Revolution, which is a bit more accessible than his other books).

Luciano Floridi

As Martin Heidegger famously said, discussing the life of Aristotle, “He was born at a certain time, he worked, and he died.” That is, when discussing philosophy, Heidegger suggests that we should discuss the ideas, not the people. Still, a brief note of orientation is perhaps worthwhile.

Luciano Floridi is Professor of Philosophy and Ethics of Information, as well as Director of the Digital Ethics Lab, at the Oxford Internet Institute, part of the University of Oxford. He has authored over 150 papers in the philosophy of information and technology, and his most recent work focuses on digital ethics. Notably, he also sat on Google’s advisory council in 2014, which discussed and digested the implications of the “right to be forgotten” ruling of the European Court of Justice.

Floridi’s magnum opus is a four-book series laying the groundwork for the philosophy of information, three volumes of which have been published. Floridi posits the philosophy of information (PI) as a first philosophy, i.e., an entire philosophical system spanning ontology, epistemology, ethics, politics and aesthetics. The impetus for this work is the observation that the digital revolution is signaling a type-shift in the way we humans understand ourselves and how we conduct our lives, as individuals and societies—a profound and irreversible change—and the concept of information is central in this shift.

Major Concepts

Now I’ll present a handful of Floridi’s PI concepts that are relevant to many of us in the information field, broadly construed. They may be interesting and useful to consider.

Levels of Abstraction

Level of abstraction (LoA), a concept from computer science, is a central method in PI. An LoA is a gathering of different aspects of a phenomenon (observables) that are considered important for the question at hand. Consider wine, for example. If taste is in question, the LoA might include mineral content, acidity and body. But if purchasing is in question, then the LoA might include price, maker and vintage. The LoA specifies what combinations of observables are possible.

The method of defining an LoA is a way to make explicit and manage one’s ontological commitments. When a question (e.g., a research question) specifies an LoA, then it is answerable; the LoA provides the syntax for acceptable answers. Floridi gives the example of Kant’s antinomies of pure reason, which do not specify an LoA and are thus unanswerable. In the information field, we see Kant’s antinomies manifest as researchers may get caught up in questions of, for example, whether something is “digital” or “analogue.” The concept of LoA gives clarity to what might be called emergent properties: on one LoA, machine learning software appears interactive and autonomous; on another LoA, the software is simply following rules specified in lines of code. Lastly, a shared LoA is necessary for cooperation in any scenario of information exchange. Consider the Mars Climate Orbiter disaster of 1999, which was caused by one firm tacitly operating in imperial units (pound-seconds) whereas the cooperating firm tacitly operated in metric (newton-seconds). As Floridi writes, “failing to specify a level at which we ask a given philosophical question can be the reason for deep confusions and useless answers.”

Infosphere

By analogy with the concept of the biosphere, Floridi posits that we are now living in the infosphere. The infosphere is the totality of information and interacting organisms (what Floridi calls inforgs). Just as the biosphere concerns what is alive, the infosphere concerns what interacts—increasingly, this substrate is digital-technologically–mediated.

Re-Ontologization

Floridi writes of a series of revolutions of self-understanding in the history of humanity: the Copernican, the Darwinian, the Freudian—and now the informational. Information technology is changing what we know, what we can know, what we think we are, and, indeed, what we are. This re-engineering of existence is what Floridi refers to as re-ontologization. As the infosphere becomes re- ontologized, our sense of space changes, as does how we work with each other. For example, we no longer “go online” or do certain things “offline”; rather, as Floridi says, we simply live onlife. Our era is also the era of hyperhistory, wherein (a) our societies depend on information technology to function, and (b) more writing is read by machines than by people. In the moral realm, re-ontologization has borne new concepts in recent years, such as doxxing, trolling and revenge porn. Another novel feature of our infosphere that Floridi flags is the decoupling of accountability and responsibility.

Ontological Friction

One important site of re-ontologization is regarding friction in the flow of information, or ontological friction. Floridi claims that the infosphere is becoming more frictionless; that is, information flows easier, but this ease is not distributed evenly. This has numerous implications. On a personal level, we find claims of ignorance less convincing, and a barrage of information can lead to hasty conclusions and even anxiety. On a systemic level, we see the rise of micrometering, new depths to the digital divide and changing notions of privacy.

Informational Identity

On an informational ontology, it becomes especially clear that a person is not simply their body, but also their information. Simply put, you are your information, which includes the pattern of energy and matter that composes your body, as well as your stories, your documents, your smartphone data, search results for your name, etc.

In an information economy (as all hyperhistorical economies are), this fact presents a danger for selfhood: “the processes of de-physicalization and typification of individuals as unique and irreplaceable entities start eroding our sense of personal identity as well.” Floridi writes that we become apt to conceive ourselves as bundles of types rather than as unique singularities, and that many of our technology-mediated activities can be read as attempts to reappropriate our selves.

Ontic Trust

In a global society riven by cultural differences, what sort of ontology could we all share? Are there any ethical principles could we hope to hold in common? Floridi proposes an “ontology lite” moral framework called the ontic trust, named after the legal concept of trust, in which one party (the trustor) settles some property on a second party (the trustee) for the benefit of a third party (the beneficiary)—so no one fully owns the property. The ontic trust, then, is such a relationship wherein the infosphere (including all agents and patients) is the property, owned by no one but passed down by past generations (donors) and cared for by current agents (trustees), for the benefit of all future and current patients and agents (beneficiaries). On this account, all informational entities deserve (at least minimal) moral respect; all beings have obligations toward each other—and even toward being as such.

Philosophers are conceptual shipbuilders. We root out the planks that are no longer serving humanity for one reason or another, and we build new features of our ship in response to the changing winds. This is not so much a matter of uncovering ultimate truths as it is crafting solutions to help us get along. Quite along these lines, Luciano Floridi, in his new book The Logic of Information, describes philosophy as conceptual design, explicitly tying philosophical inquiry with the discipline of design.

Philosophers are conceptual shipbuilders. We root out the planks that are no longer serving humanity for one reason or another, and we build new features of our ship in response to the changing winds. This is not so much a matter of uncovering ultimate truths as it is crafting solutions to help us get along. Quite along these lines, Luciano Floridi, in his new book The Logic of Information, describes philosophy as conceptual design, explicitly tying philosophical inquiry with the discipline of design. I recently made bigos, a hearty Polish stew, using the recipe I got from my friend’s mother. I’ve loved bigos ever since I first had it at her house, back when I was studying abroad. The recipe has three ingredients: sauerkraut, ham hocks, and dried mushrooms. But bigos is a kind of kitchen-sink dish; you can add whatever you’ve got wilting in the fridge that you need to use up. Bigos really hits the spot for me, especially on cold winter days. But I wouldn’t call it pretty.

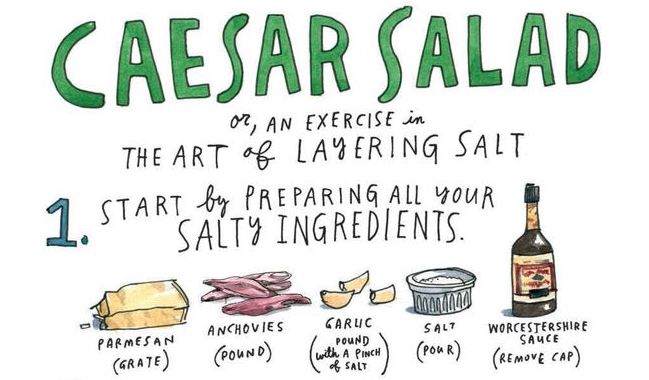

I recently made bigos, a hearty Polish stew, using the recipe I got from my friend’s mother. I’ve loved bigos ever since I first had it at her house, back when I was studying abroad. The recipe has three ingredients: sauerkraut, ham hocks, and dried mushrooms. But bigos is a kind of kitchen-sink dish; you can add whatever you’ve got wilting in the fridge that you need to use up. Bigos really hits the spot for me, especially on cold winter days. But I wouldn’t call it pretty. There’s a handful of cookbooks in my kitchen. They, too, are for the most part adorned with luscious photographs. When I peruse them, looking for a weekend project or something to cook for company, I even find myself skipping over the pages with no photos. Other times, the photos are intimidating. I might see a photo and think to myself, “That looks way too involved for me right now,” or, “I could never make it look like that,” which likewise makes me turn the page. It’s probably a familiar feeling. Like that pitiable and brave soul who tried to make Cookie Monster cupcakes, perhaps it makes you not want to try again.

There’s a handful of cookbooks in my kitchen. They, too, are for the most part adorned with luscious photographs. When I peruse them, looking for a weekend project or something to cook for company, I even find myself skipping over the pages with no photos. Other times, the photos are intimidating. I might see a photo and think to myself, “That looks way too involved for me right now,” or, “I could never make it look like that,” which likewise makes me turn the page. It’s probably a familiar feeling. Like that pitiable and brave soul who tried to make Cookie Monster cupcakes, perhaps it makes you not want to try again.