“A map is not the territory,” goes the famous dictum. In other words, a representation is different from the object it represents. It’s obvious, right? And yet I’m not so sure anymore.

Lately I’ve been wondering about the relationship between a document and object it documents. As Michael Buckland has written, some documents are made as documents, wherein the object precedes the document (e.g., a database record describing a movie); while others are considered as documents, where the document precedes the object (e.g., the Liberty Bell as a sign of Abolition). And the link between the document and its object may be a matter of physical resemblance, socially controlled, or idiosyncratic.

All this suggests a one-way relationship between document and object—most typically, an arrow going from territory to map. But things seem to be getting more complicated. Or maybe things were always more complicated, but new kinds of documents are revealing complications that have long been hidden.

What I see happening in the digital world are three related trends:

- We are increasing the size of the map.

- We are becoming more interested in the map than the territory.

- The map is redrawing the territory.

Let’s consider each in turn.

The first is fairly obvious. We are documenting more, and in more detail, than ever before. If we look at maps narrowly defined, it’s clear that any web-based map packs in more information than any paper map could. You can zoom in or out quite far, you can navigate the whole world, you can see construction and traffic, businesses and buildings of all stripes are labeled, and on and on.

In a recent Wired article, Kevin Kelly discusses our growing map. Mirrorworld, he says, is the next major digital platform (after the web itself). “Someday soon, every place and thing in the real world—every street, lamppost, building, and room—will have its full-size digital twin in the mirrorworld.” When a map becomes sufficiently detailed, after all, it is essentially a mirrorworld. Kelly points to our AR technologies at present—from Pokémon Go to camera-based Google Translate, as a mere figment of what is to come. Google Maps is crude in comparison.

Second, in the age of the growing map, we are becoming more enthralled with the map than ever before. Susan Sontag was an early observer of this. In her essay “The Image-World” (part of her excellent On Photography), Sontag wrote that, whereas Plato taught us to look at reality rather than images, nowadays we seem to embrace images over and above the real. “An image-world is replacing the real one.” In other words, we prefer the map to the territory. For example, if we see images of a person or place before seeing that person or place in the flesh, the real thing often disappoints.

Prescient, Sontag wrote, “Cameras define reality in the two ways essential to the workings of an advanced industrial society: as a spectacle (for masses) and as an object of surveillance (for rulers).” Walking down the street of any city today, one is struck by how many people are looking down at their smartphones, rapt by the growing mirrorworld—a spectacle indeed. Meanwhile, as Shoshana Zuboff has made clear in her The Age of Surveillance Capitalism, the mirrorworld thrives on surveillance and the sale of behavioral futures.

But we don’t live in the mirrorworld (a la Wall-E) just yet; we still flit between the image and the real. And so the map changes our understanding of the territory. It shows us our world in a different light. Seeing a map could show a shorter route from A to B, to give a simple example. And another favorite example of mine was given by Nicholas Mirzoeff: Once the image “The Blue Marble,” a photograph of the whole earth from space, was published, people experienced what’s called the overview effect, a different sense of what it means to be an inhabitant of the earth. This leads into the final trend.

Third, and maybe most interestingly, the map is redrawing the territory. Luciano Floridi has coined the term re-ontologization, which refers to how the digital changes the physical. For example, the digital has borne new concepts, such as trolling, doxxing and revenge porn; and it has decoupled concepts that have historically always come together, such as responsibility and accountability. With re-ontologization, what is happening to the relationship between the map and the territory? One example that comes to mind is the way that smartphone maps, which navigate based on real-time traffic, actually change the traffic that they represent. Once-sleepy residential streets are now bumper-to-bumper because they offer a shortcut to the highway.

But we should not make the mistake of defining “map” too narrowly, lest we miss the forest for the trees. Alfred Korzybski, who coined the map–territory dictum, used the word map only as an analogy; what he was talking about was semantic representation writ large, encompassing human language and all symbolic thought.

So when we think about the map rewriting the territory, we should think about all documentary phenomena, and the links between documents and their objects. What is the relationship between a person and their online persona(s), for instance, and how does one form the other? Korzybski wrote that “the ideal map would contain the map of the map, the map of the map of the map… endlessly.” If a mirrorworld is on the horizon, we need to map the map.

I’m reminded of a vignette from Lewis Carroll’s last novel, Sylvie and Bruno Concluded, written in 1893:

“That’s another thing we’ve learned from your Nation,” said Mein Herr, “map-making. But we’ve carried it much further than you. What do you consider the largest map that would be really useful?”

“About six inches to the mile.”

“Only six inches!” exclaimed Mein Herr. “We very soon got to six yards to the mile. Then we tried a hundred yards to the mile. And then came the grandest idea of all! We actually made a map of the country, on the scale of a mile to the mile”

“Have you used it much?” I enquired.

“It has never been spread out, yet,” said Mein Herr: “the farmers objected: they said it would cover the whole country, and shut out the sunlight! So we now use the country itself, as its own map, and I assure you it does nearly as well.”

Indeed, a mile-for-mile map would swallow us up. The only way for it to be “really useful” would be for us to live inside it, wherein the map is less a map than part of the territory itself.

I’m especially struck by the last line. When the map is so big that it swallows us up, will we not find that we’re simply better off without it?

I recently made bigos, a hearty Polish stew, using the recipe I got from my friend’s mother. I’ve loved bigos ever since I first had it at her house, back when I was studying abroad. The recipe has three ingredients: sauerkraut, ham hocks, and dried mushrooms. But bigos is a kind of kitchen-sink dish; you can add whatever you’ve got wilting in the fridge that you need to use up. Bigos really hits the spot for me, especially on cold winter days. But I wouldn’t call it pretty.

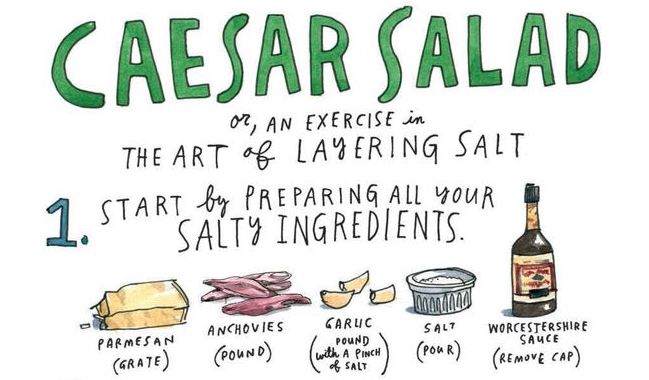

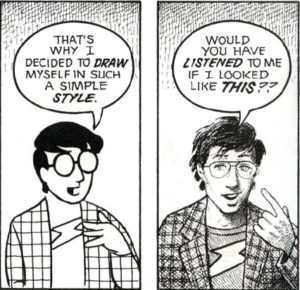

I recently made bigos, a hearty Polish stew, using the recipe I got from my friend’s mother. I’ve loved bigos ever since I first had it at her house, back when I was studying abroad. The recipe has three ingredients: sauerkraut, ham hocks, and dried mushrooms. But bigos is a kind of kitchen-sink dish; you can add whatever you’ve got wilting in the fridge that you need to use up. Bigos really hits the spot for me, especially on cold winter days. But I wouldn’t call it pretty. There’s a handful of cookbooks in my kitchen. They, too, are for the most part adorned with luscious photographs. When I peruse them, looking for a weekend project or something to cook for company, I even find myself skipping over the pages with no photos. Other times, the photos are intimidating. I might see a photo and think to myself, “That looks way too involved for me right now,” or, “I could never make it look like that,” which likewise makes me turn the page. It’s probably a familiar feeling. Like that pitiable and brave soul who tried to make Cookie Monster cupcakes, perhaps it makes you not want to try again.

There’s a handful of cookbooks in my kitchen. They, too, are for the most part adorned with luscious photographs. When I peruse them, looking for a weekend project or something to cook for company, I even find myself skipping over the pages with no photos. Other times, the photos are intimidating. I might see a photo and think to myself, “That looks way too involved for me right now,” or, “I could never make it look like that,” which likewise makes me turn the page. It’s probably a familiar feeling. Like that pitiable and brave soul who tried to make Cookie Monster cupcakes, perhaps it makes you not want to try again.