In literate societies like ours, it’s easy to come to the conclusion that writing equals language. When we talk about “knowing a language,” for example, we generally assume that the person can read and write—not just speak.

Even so, writing is not language—it’s just a representation of language. And moreover, it’s imperfect, which is why we often talk about “reducing” a language according to orthographic rules. English is a shining example of this: Each written vowel and many consonants can be pronounced in several ways, and some letters sound the same, depending on their context. Despite how we talk about the whimsy and nonsensicality of English spelling, it is a system—it’s just a bit distinct from the system of spoken English. Other writing systems are even more distinct from their spoken counterparts.

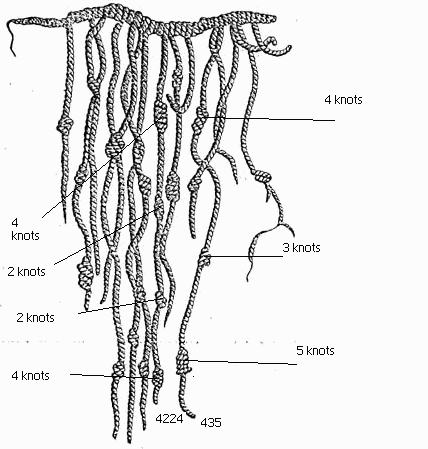

Writing and speaking are also distinct for another reason: Writing has to be taught, but speaking is learned naturally. In other words, the primary manifestation of language is spoken, not written. After all, the written word only has a voice for those who can decode it. Moreover, literacy has been anything but widespread over the course of history. According to Mateo Maciá in his book El bálsamo de la memoria, of the thousands of languages that have existed in all of humanity, only 106 have been written. Of today’s three thousand spoken languages, only 78 have produced written texts.

Linguistics, therefore, would be too narrowly defined if it focused only on written language. And because writing is a symbolic representation of language—not language itself—it would be limited in the conclusions it could draw. Because of this, some linguists have rejected the idea of analyzing writing at all. Ferdinand de Saussure comes to mind.

But if linguistics were to reject writing entirely, it’d be missing out big time:

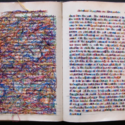

- First, languages that predate sound recording have come to us only through texts, and they’re certainly worth studying from a linguistic perspective.

- Second, writing and language mutually influence each other. For example, think about the word “comfortable.” If you’re like most speakers (at least in America), you pronounce it something like comf-ter-bl. Every once in a while you’ll hear someone pronounce it com-for-ta-bl, and it may strike you as a bit weird, even if you’re not sure why. Judgments aside, we can be sure that this pronunciation comes from the way the word is spelled.

We should study writing from a linguistic perspective because it can show us things that we’d miss out on otherwise. But we must be careful, because it’s not the same as language.

Follow

Follow