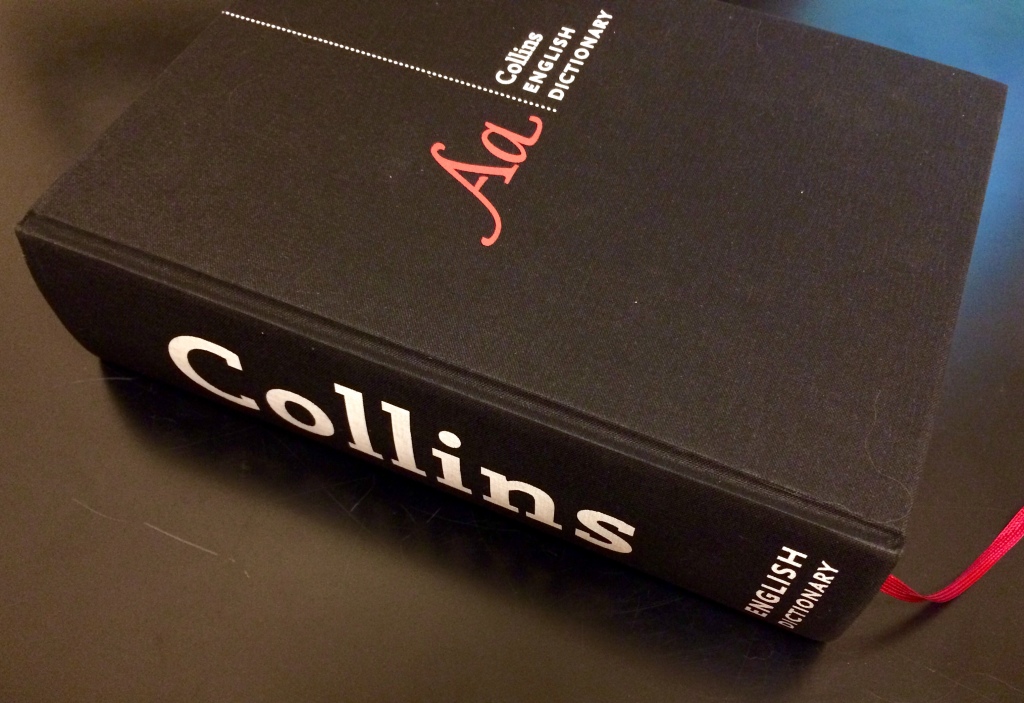

I’ve wanted a hardbound dictionary for a while now. It’s a bit of a long story, but if you’re interested, don’t miss the second part of this post, below. I recently received a review copy of the new 12th edition of the Collins English Dictionary, and it made my day (and week, and maybe life).

But what’s the fuss about a physical dictionary? Surely a print dictionary in the digital age is nothing more than a quaint anachronism. Though as a writer I consult the dictionary many times a day, I have long preferred online dictionaries—and, more recently, the one accessible directly through Spotlight in Mac OS X. (But don’t get me started on how Yosemite has made accessing the dictionary in this manner much more difficult. Shame on you, Apple!) Electronic dictionaries are faster and easier to access and sometimes more extensive. They’re also easier to publish and update, certainly.

I think electronic dictionaries are great for getting information. In and out. You know what you want, you find it, and you leave. In the framework of document transaction, electronic dictionaries are great for efferent, pragmatic experiences. So I ask again: What is the role of a print dictionary in today’s world?

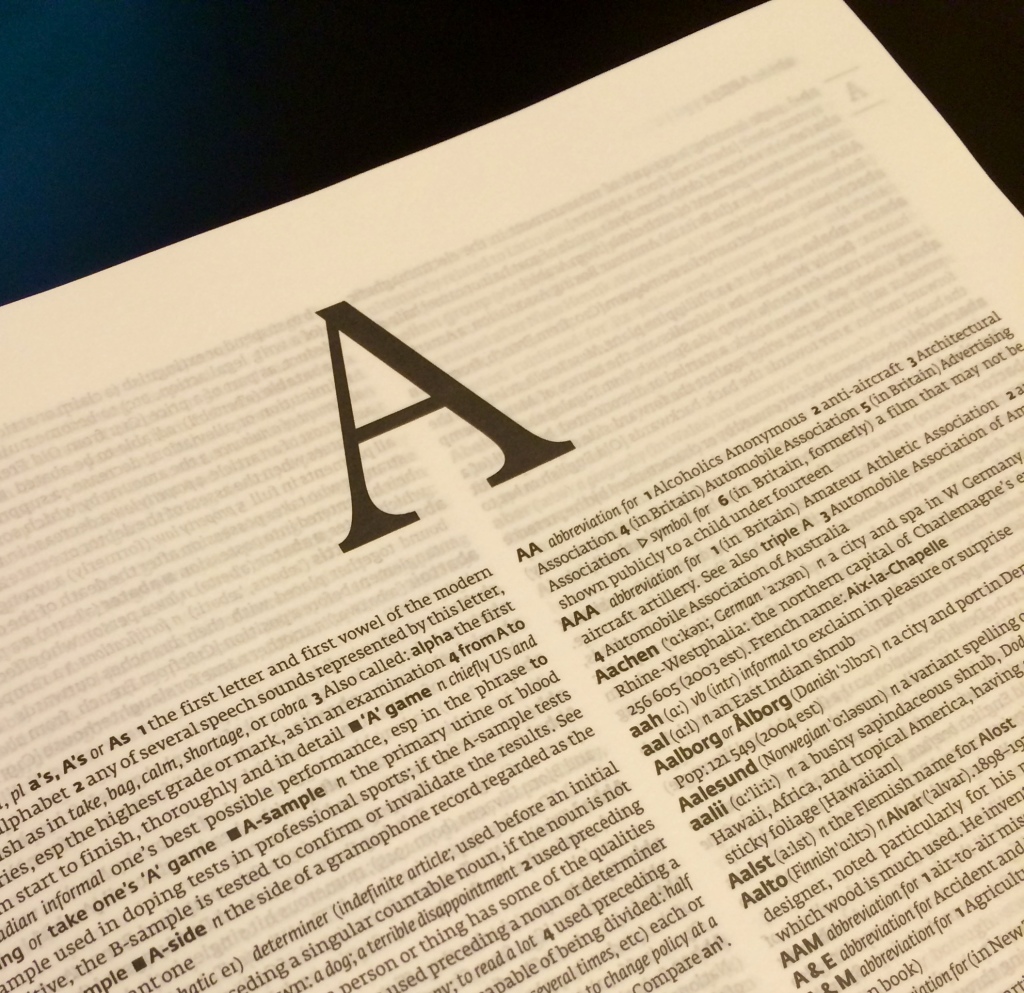

Though if you wanted to know what nark means you could conceivably turn to a printed dictionary for that information, an electronic dictionary would probably serve you better (it’s faster, after all). Granted, some people surely still prefer print dictionaries even for such clinical operations. Print dictionaries excel somewhere else: They facilitate exploration. They encourage serendipity. They allow you to turn to a random page and see what delights await in a way that electronic dictionaries simply cannot.

Sure, there’s any number of “word of the day” newsletters and, for that matter, the Wikipedia Random Article feature attempts to serve this end, but there’s just something different about the physical act of exploration and discovery. I’m not sure exactly what that is, but I know it’s there.

And this has been an important aspect of print dictionaries not only as they exist alongside electronic ones, but since their very origin. As Mark Forsyth says in the wonderful prologue to this edition, “The Joy of Dictionaries”:

Most importantly [the publication of the first dictionary in 1604] was the first time that an English man or woman could sit down and browse. The delicious pleasure of reading words that don’t have to make a sentence or story, but are simply beautiful and interesting by themselves.

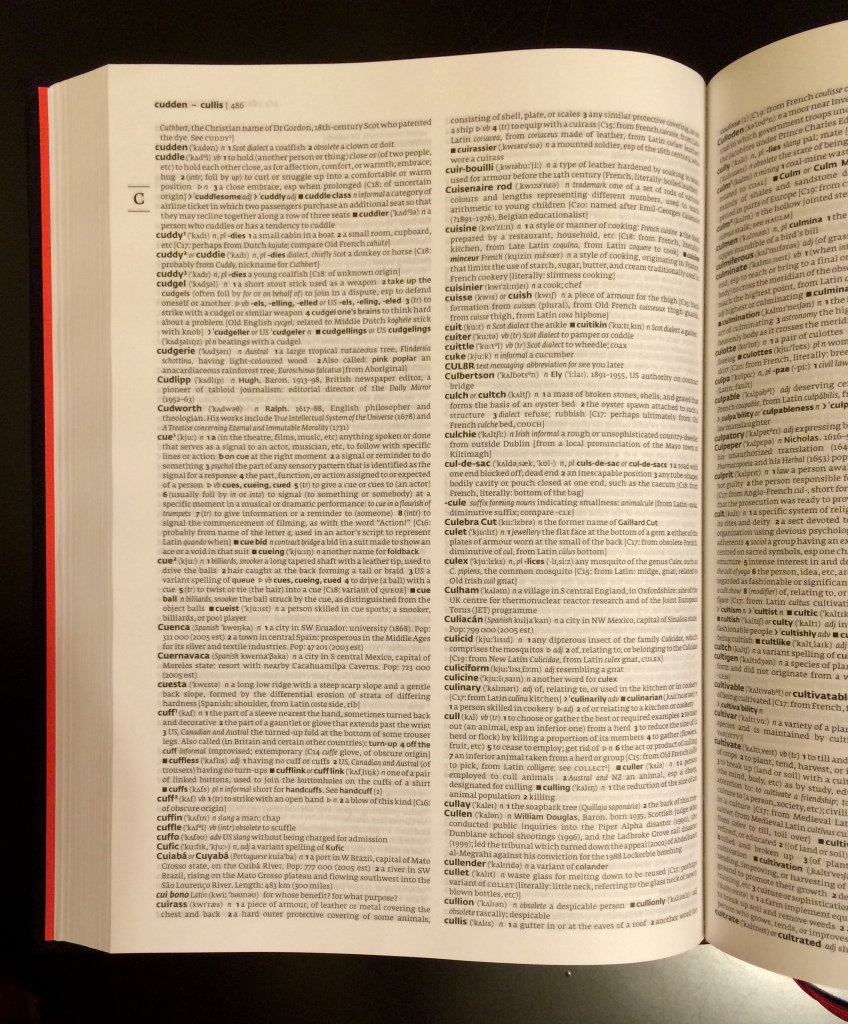

I should also mention that dictionaries are also wonderful artifacts. The Collins 12th edition—the largest single-volume English dictionary in print, and this edition includes over 50,000 additions—is a handsome black tome with white and red accents. The clothbound cover feels great in the hands. It smells amazing. The leaves are crisp. The print, though small, is legible and all around delightful.

And not to mention the pronunciations listed are great for helping me hone my proper London accent.

For the Want of a Dictionary

I wrote the essay below for my 12th-grade Language and Composition class. It describes what I regarded (and still regard) as a terrible treachery, which has thankfully since been righted (see above).

We are healed of a suffering only by expressing it to the full.

Marcel Proust

The arrival of the interclass mail lady is something that nearly every student at Hartford Union High School looks forward to every day, every hour. It’s usually a disappointment, though, seeing that if a student is fortunate enough to receive a piece of mail (a very slight chance), it’s usually something boring or unwanted. In any case, when the mail lady sidles through the classroom door, all the pupils’ eyes avert their dry gaze from the teacher and eagerly espy the mail lady’s parcels, trying to see who they’re for.

Sometime in early April 2004, I sat quietly in Mr. Lane’s sixth-hour Honors Geometry class, trying to stay awake. The topic of the lesson on that particular day has escaped me, but the more important event of the hour certainly has not. That event, like the most important event of most class periods, was the arrival of the mail lady. When she walked in, her bushy black hair bouncing as she walked toward Mr. Lane, she carried a thin stack of half-sheets and envelopes, and my eyes lit up. I didn’t seriously consider, though, that I would receive anything, but my curiosity couldn’t help but spark.

Mr. Lane accepted some of the half-sheets and envelopes, flipped through them, and muttered a quick “thank you” as she turned to leave. He began distributing the mail to the usual suspects, and I thought nothing of it but felt a deep, ineffable longing to receive a piece of mail, just once. To my surprise, and to wake me up, Mr. Lane plopped a regal-looking envelope in the center of my desk. The words Timothy Gorichanaz, 6/214 were neatly scribed on the face of the envelope and, considering it, to tear such a pretty thing open seemed outright monstrous.

I examined the front and back of the envelope; the paper was marbled and expensive and the return address was American Association of University Women. “Why ever would such a group seek to contact me?” I wondered. Interested, I opened the envelope and unfolded the enclosed letter. Skimming it, some grand words leapt into my vision. In disbelief, I read it more slowly, from top to bottom, and absorbed what it told me. I cannot recall, of course, the exact wording, but it went something like:

Dear Timothy Gorichanaz,

We are pleased to announce that, due to your amazingness, we would like to invite you to join us at the Rotary Honors Student Banquet in May. At this banquet we honor outstanding students, including the students with the ten highest GPA’s of their class, and also the senior Rotary Students of the Month. We would like you to attend, blah blah blah, and your meal is free. A letter will also be sent to your house, and your parents will have the opportunity to buy meal tickets.

The wording on the actual letter was slightly more eloquent, but that’s about all it said. Giddy, and slightly confused, I read the letter again and again and paid no attention to Mr. Lane’s babbling about vectors or angles or whatever he might have been talking about, and nobody else in the class knew my excitement—except perhaps Adam, who sat next to me and read the letter as I did.

Elated, I showed the letter to my parents who, as expected, were quite proud. I knew that I did well in school—a trend that began in early elementary school—but never in my wildest dreams did I think I would be among the top ten students in the class.

I attended the banquet in May, with only a bit of nervousness, as I hardly knew anyone else in my class at the banquet. The dinner was great and the speaker was boring, but I persevered—and good thing I did.

The Honors Students were called up by grade, freshmen first, to receive their plaques and get a picture taken for the newspaper. We stood proudly and held our plaques with toothy smiles, and then returned to our seats. Sophomores next, then juniors, and finally: seniors. As I was following the events of the Banquet in my program, I noticed several of the seniors’ names had a tiny asterisk after them, which denoted “Four-Year Honors Students.” With my skills of deductive logic, I decided that these Elite Few must be the students who attended this banquet every year. “That might be cool,” I thought, as I envisioned myself standing up there one day. Yes, there was a point when I the thing I longed for most was to receive a tiny little asterisk after my name.

As it turned out, the elite seniors got much more than just an asterisk in the program; the Four-Year Honors Students received, to my jealousy, a huge red-bound Dictionary that had to be carried with both hands. As soon as I saw those students receive their dictionaries, I made it a goal: in May of my senior year, I would stand up there, shaking the principal’s hand as he gave me one of those fabled red-bound tomes. Though I would likely never use it—I’ve been a daily user of www.dictionary.com since middle school—it was an idol for me, and I always strove to achieve that goal and earn that idol. I grew feverish for a Dictionary. All I did in school pushed toward that goal: the future reception of Le Grand Dictionnaire.

As the years passed, I received exemplary grades, wrote wonderful papers, and articulated enticing speeches. Sophomore year was a breeze. Though I took eight credits, I did exceedingly well in each class. I had just enough honors classes to boost my GPA enough to receive my second April Invitation (an A in an honors class counted as 15 points, while an A in a normal class counted only as 12), though my class rank slipped from Third to a meager Fifth.

I nearly jeopardized my Dictionary-filled future, though, when I signed up for my junior year classes. I’m not sure what I was thinking, but I only took one honors class: pre-calculus. I was convinced that having only one honors class would surely push me out of the top ten. I worked hard, though, to make up for it, all year and received mostly all A’s, except of course the B+ in pre-calculus. My hard work paid off and I was delighted to receive my third invitation in April; I was Eighth.

Well, I thought, I made it so far, and I wouldn’t allow my measly senior year foil my Dictionary plans. When I signed up for my senior year classes, I made sure I had all honors classes, which would ensure an outrageous GPA—closer to 15.0 than to 12.0. Surprisingly, my schedule worked out, and I was able to attend all the classes of my choice: seven honors courses, including five AP courses.

I went into my senior year expecting loads and loads of homework every night but, to my delight, the homework was manageable. I received straight A’s for the first semester, and ended the second quarter with a 14.3 GPA. Certainly I would receive a Dictionary that spring.

Little did I know, the Universe was conspiring against me. I received my April Invitation this year during Advanced Biology fourth hour, and the first thing I noticed was that the letter arrived as a tri-folded sheet of plain white paper. No fancy marbleized paper or even an envelope. Not letting this distract me, I opened the letter and read the familiar phrases, smiling and nodding to myself as if to say, “I did it!”

The other members of the Elite Few and I gathered in silent elation, knowing that our coveted Dictionaries were now secure. All that remained was to wait until the Banquet in May, and gossip what it might feel like to finally achieve our goal.

Mixed in the giddy conversation, however, were some words of concern: the Banquet, which had always been held at the Chandelier Ballroom, was to be held at the Schauer Arts Center this year. Nothing against the Schauer Center, of course, but something inside me suggested that budget cuts were seeping their way into our private Honors Celebration. Also, instead of a Banquet, this year’s celebration was to be a “Meeting” with hors d’oeuvres rather than the catered meal we had gotten used to.

Some of the students who weren’t able to attend the Banquet all four years—because they had missed a year or two—suggested, jovially but gravely, that perhaps we wouldn’t receive any Dictionaries, that perhaps budget cuts would throttle and kill the Dictionary Fund which we so greatly relied on. I would hear none of it.

Walking into the Schauer Center on May 2 with some of my peer Elitists, I experienced shivers and jitters that cried, “Dictionary!” I was unable to constrain myself and my knees and jaw chattered as I sat in my chair. Dictionary! When I entered the Lodge, though, a shockwave swept my body. As I scanned the table at the front of the room, I did not see any Dictionaries. In all the past years, the Dictionaries had been proudly displayed in a grand stack. “Perhaps they are in a box on the floor,” I thought to myself, trying to stay optimistic.

When my name was called, I leapt from my seat and jogged to the front of the room, received my plaque, and stood in line with the other seniors. Then came the announcement about the Four-Year Honors Students, and my name was mentioned as an evil man handed me a tiny white box. “Thank you,” I muttered as I walked back to my seat. Clearly the box did not contain a Dictionary; it was too small, and moreover I did not hear choirs of angels pronouncing Ave Diccionaria! I hoped some sort of mistake had been made.

Sitting down, I saw that the box read, “Four-Year Honors Gift.” No Dictionary, it seemed. I opened the box and the wood-encased pen fell into my palm. A pen?! What a travesty! Unforgivable! Four years of hard work to maintain excellent grades, all in the name of a Dictionary, and what do I receive in the end but a measly pen. And to make matters worse, I discovered that the recipients of the Rotary Scholarship received the exact same pen as the Elite Few. I returned the pen to its case and tossed it on the floor. I didn’t want to look at it.

For the next few days, I moped and moped. All that work, for naught. My sole ambition to get good grades turned out to be a sick ruse, and I was enraged. I could not believe that the Rotary Club of Hartford, Wisconsin would dare to pull such a prank on the Elite Few, but it turned out that it was no joke. They earnestly expected us to be happy with a pen. They had no idea.

As I passed through various stages of depression regarding the Great Deception, I realized something: I received a touch more than a stupid pen that day. I received an asterisk.