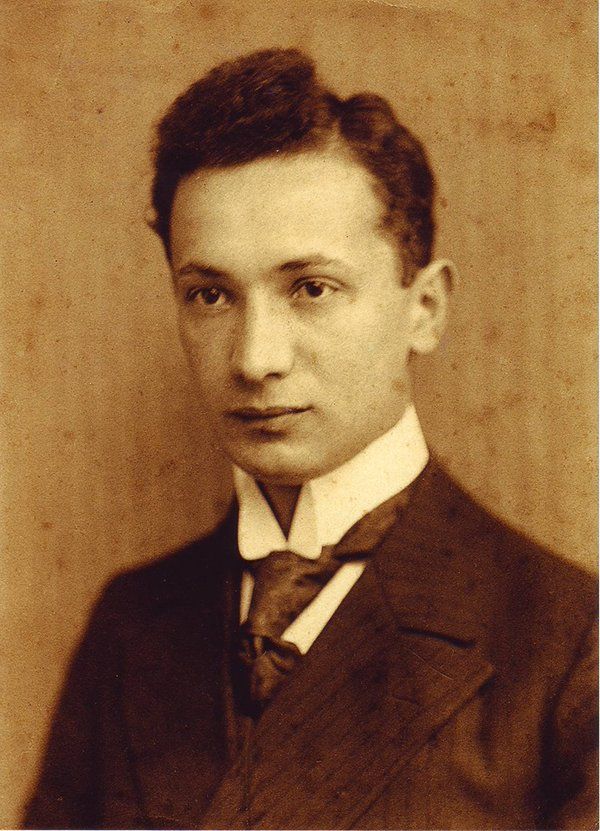

One of my favorite philosophers is Martin Heidegger (1889–1976). His work has influenced not only my scholarship, but also my worldview. The notion that human being is inextricable from the world, the concept of the “they-self” who we are when we follow the stream of society, the vision that our death gives meaning to our life, the idea that modern technology coerces us into seeing the world in terms of resources to be exploited, the understanding that thinking is a form of thanking… His insights really are numberless.

Heidegger is in a very strange position nowadays. On one hand, he is hailed as one of the most influential philosophers of the twentieth century, but on the other there is a palpable cone of silence around his name. There’s a mostly-unspoken notion that perhaps one shouldn’t engage with his ideas—or, God forbid, cite him. (Though I have to think he’s not too worried about his h-index.) The elephant in the room, to put it sensationally, is that Heidegger was a Nazi.

I saw a post on Twitter earlier this year that read, “Given that Heidegger was a Nazi, who should I cite for the concept of breakdown?” First and foremost, such a question strikes me as a form of academic dishonesty, though I do understand the impulse comes from a good-hearted place—not wanting to support a hateful regime. It reminds me of when I read Robert Sokolowski’s Phenomenology of the Human Person, which comes to the same substantive conclusions as Heidegger in Being and Time and yet only mentions Heidegger glancingly and tangentially. In my opinion, we should give credit where it’s due, whether we like where it’s due or not.

Anyway, I read and cite Heidegger quite a lot in my own work, and I thought it would be worthwhile to reflect on my doing so. Particularly now, as there is a way of thinking that is becoming more prevalent: a tendency to take people as one thing only—you’re either with us or against us—not recognizing that, as Alexander Solzhenitsyn put it, “the line dividing good and evil cuts through the heart of every human being.” This is the impulse that leads people to topple statues commemorating historical figures who, notwithstanding any of their virtues, committed the sin of holding slaves. Amartya Sen argued that such a “solitarist” approach to identity is fallacious and harmful—and yet it is apparently so enticing to us that we slip into it again and again.

Saying “Heidegger was a Nazi” gives quite a particular impression, and the first question we should ask is whether that impression is true. This has been widely discussed, and I don’t want to rehash all that discussion here, but some broad strokes are warranted. In the end, my own conclusion is that Heidegger was more a coward than anything.

Heidegger was a professor at the University of Freiberg and joined the Nazi party in 1933, becoming rector of the university (i.e., president). In this role, he was responsible for removing Jewish faculty from the university, for enforcing quotas on Jewish students, implementing race-science lectures, etc. Adam Knowles, my colleague at Drexel, has written that Heidegger carried out these duties with efficiency. A year later Heidegger resigned from the rectorship and stopped participating in Nazi activities, though he never formally left the party. Beside all this is the fact we have to contend with that, as a philosopher, Heidegger worked with and inspired a slew of Jewish philosophers with whom he had friendly relationships, such as Hannah Arendt and Hans Jonas—and not to mention his advisor Edmund Husserl.

Then there’s the issue of Heidegger’s infamous notebooks. Throughout his life, Heidegger kept philosophical notebooks in which he recorded ideas and observations. The publication of these notebooks caused a renewed (and sensationalized) interest in the questions of Heidegger’s Nazism, as they contain certain anti-Semitic snippets. But these comments should not be mistaken for reflective philosophical views; for a philosopher, a notebook is a tool for thinking, for playing with ideas, for exploring. We should be careful in attempting to infer one’s beliefs from their writings in philosophical notebooks.

But even if we do suppose that Heidegger was a dyed-in-the-wool Nazi, should that matter? A thorny question if there ever was one. Nazi scientists made a number of scientific discoveries, sometimes through unethical research on human beings. Whether and how such findings should be used is difficult to say. The antimalarial drug chloroquine, for instance, was originally developed using human subjects in concentration camps. Should we do away with it? How do we account for advances made since after World War II? The problem with science is that it cumulates.

Knowledge gained through coercive and unsafe research is one thing, but what about desk research funded by the Nazi regime? For instance, Fanta was developed in Nazi Germany. Should we stop drinking it? When it comes to philosophy, perhaps, the relevant question is whether the philosophy is somehow sympathetic with Nazism. On that question, with regard to Heidegger, a regiment of philosophers can be marshaled both for and against. It is anything but clear. And so how to rule in such a case? To me, it begins to look much more like a typical ad hominem fallacy. In my view, philosophical arguments should be assessed on their own merits, not on the basis of who said them. Heidegger himself seems to have held the same view; when tasked with recounting the life of Aristotle, he gave one sentence: “He was born at a certain time, he worked, and he died”—because that’s all that matters, when the subject is Aristotle’s philosophy. But I do wonder if, as time goes on, we are finding ad hominem arguments more and more persuasive. It seems to me that, societally, we’re having quite a difficult time separating people from ideas.

Another consideration: Should we expect our philosophers to be morally good? (To be sure, I think we should expect everyone to be morally good, but I guess the question is whether we should expect more of philosophers than of others.) In ancient times, when philosophy was more clearly understood as guidance for how to live a good life, perhaps the answer was yes. But in modern philosophy, there seems to be a disconnect. Arthur Schopenhauer (1788–1860) was a famous misogynist and once pushed a woman down a flight of stairs, and Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889–1951) was a tyrannical and abusive schoolteacher. John Searle (b. 1932) allegedly sexually harassed, assaulted, and retaliated against a student while a professor—and not to mention earlier, as a landlord, played a major role in large rent increases for students at his university. A 2019 study found that philosophy professors by and large do not behave any more morally than other academics. (There’s an exception, evidently, when it comes to vegetarianism.)

Is it fair, then, to malign Heidegger and give all these other philosophers a pass? We might recall the Christian maxim here: “Let the one who is without sin cast the first stone” (John 8:7).

Follow

Follow