We’ve talked before about the two-pronged nature of names; they’re both aural and visual. Today, let’s consider solely the visual—the physical. We often confront the physical power of names, though I think we generally take it for granted.

As the old adage goes, if you can call something by name, you can command it—have power over it. But merely writing a name does not seem to have the same effect; perhaps it is even the other way around: By physically recording the name of something, it gains power over you.

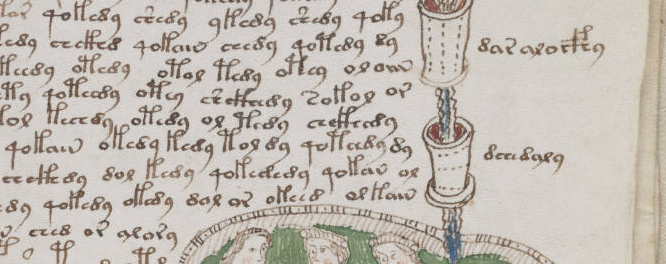

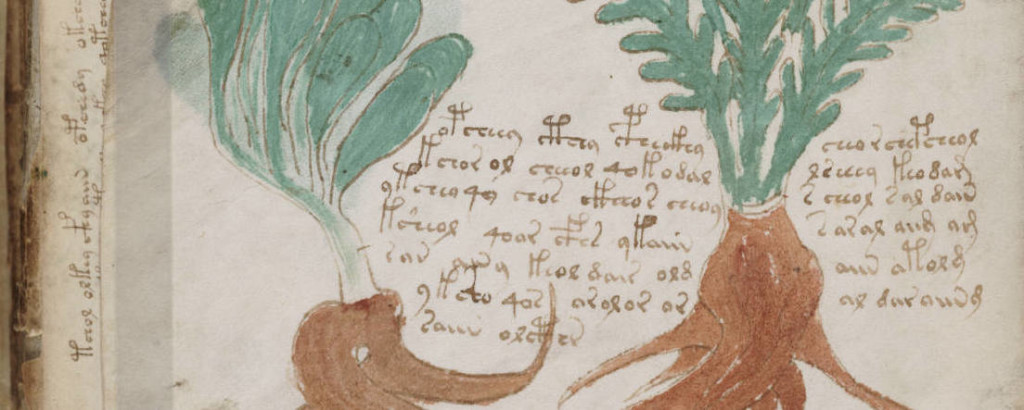

God is as good a place to begin as any. In the Hebrew Scriptures, God is called יהוה (these Hebrew characters can be transliterated as YHWH). The curious thing about this name is that it exists primarily visually—today, we do not know its exact original pronunciation; YHWH lacks the vowels necessary for pronunciation. (In modern Hebrew, vowels are denoted by diacritic marks above or below the consonants, but these were not used in ancient times.) Was it Yahweh, or perhaps Yehwoh? Yihwah? Yuhwoh? You get the idea. At first it may seem that the missing vowels are inconsequential, but consider that it would only take a single missing vowel in English to spell the difference between lit, lat, lot, loot and late, five completely different words.

But even back when they knew how to pronounce it, the name of יהוה was considered too powerful to be uttered aloud—except once per year by the High Priest in the Holy of Holies. For common reference, יהוה was given the name Adonai. As a result, the characters יהוה took on a decided visual power—and mystery, seeing as, in time, its pronunciation was forgotten. Then it is perhaps not coincidental that, given that יהוה was not to be commanded, neither was He to be named. Out loud, at least. For the name of יהוה has lived on in its physical form. To be loved, to be feared, to be worshiped.

Another manifestation of the physical power of the name of God comes from the Roman emperor Constantine the Great, who, on the eve of battle, was visited in a dream and told, “By this sign, you will conquer.” The sign, of course, being a rendition of the name of God (or, more precisely, Christ): ☧. Some might interpret the dream’s message as merely saying, “Fight in God’s name, and you will be victorious,” but the Greek phrase ἐν τούτῳ νίκα, to which the original Latin in hoc signo vinces has historically been linked, references a physical item. This sign, which made its way first onto the standards and shields of Constantine’s soldiers and then onto coins and stoles as it spread throughout the world, accompanied the spread of Christianity itself—and the God it represents.

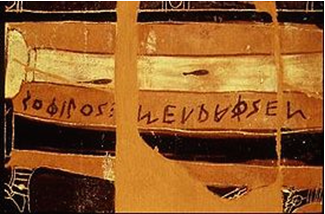

Art is another place we confront the visual power of names. Nearly every piece of art nowadays is signed. But it wasn’t always so: Sophilos, a 6th-century-BC Greek, was the first artist we know of to sign his work, pictured above. What prompted this? It could be nothing but pride—the wish to identify oneself as the artist, as the person with the power to create. Since Sophilos’ day, artists have stylized and refined their signatures in order to increase the power of these signs. Think of Picasso’s iconic signature, varying very little from picture to picture. Think of our signatures today, used as identification and validation, their value in their uniqueness and reproducibility. In this same light, what is a brand’s trademark, obsessively tooled and ever-consistent, if not a power statement?

One venue of artistic signature that I find particularly alluring is that found in East Asian ink wash painting. Though these works are done in black—and only black—ink on paper, the most virtuosic painters managed to convey the whole spectrum of tonal value. The glaring exception to the black-only rule, of course, is the presence of the red seal—the artist’s signature. Yes, the seal is usually placed as part of a pleasing overall composition, but there’s no question that the use of red, rather than black, is a symbol of pride and power. In fact, the very writing system used within the seal itself is a show of power; the so-called seal script, long since obsolete as a means of normal writing, has been most prototypically used in royal inscriptions for at least 2,000 years.

Note, too, the practice of enclosing the signature in a ring, or at the very least arranging the characters in a self-contained square or oval. This recalls the Pharaonic cartouches of Egypt—in which a Pharaoh’s name is written within a vertical oval. Much like Chinese seal script, the Egyptian hieroglyphics themselves constituted an entire writing system dedicated to the show of power, while the common people used another script to represent the same spoken language.

Jumping a few centuries to a contemporary of our own, let’s consider danah boyd, a researcher in media and communications. She’s legally changed her name to all lowercase, an alteration that did not affect the pronunciation at all—in other words, it was purely visual. One of her reasons for the change was to preserve the visual symmetry in “danah,” which is interrupted when the D is capitalized. As I’ve written about before, copy editors everywhere have deferred to her will—and thus, perhaps unwittingly, she has asserted her power over us users of the English writing system.

We take it for granted that written names are to be pronounced. As we’ve seen with יהוה, pronunciation is not always possible. More often, it is possible but quite difficult. Take Japanese personal names, which are onerously complicated because of the nature of the Japanese writing system. Say you wanted to name your son Hiroto. In katakana, the Japanese phonetic script, this is written ヒロト, but you’d likely give your son a name in kanji, the Chinese characters. Most commonly, you’d write Hiroto in one of the following ways: 浩人, 博人, 博土, 弘人 or 洋人. But you could just as easily and reasonably write it as 優斗, 優翔, 博登, 博音, 啓人, 大斗, 寛仁 or any of dozens of other possibilities. Now let’s take the reverse: Say you come across a person named 優翔. There’s not much about these characters that hints at their pronunciation; this pair could be pronounced as Yuka, Yuto, Yushou, Yuuka, Yuuto, Yuushou, Hiroka, Hiroto, Hiroshou, Masaka, Masato or Masashou. And that’s assuming you know it’s a male name—if it’s possibly female, there’s a whole host of additional possibilities. Hence the practice in modern Japan of providing your name’s pronunciation with its spelling when filling out forms.

What does this all mean? If the purpose of a name is to identify and differentiate, then part of the power of a name, in literate society, relies on its visual identity. When the visual side of a name is so far removed from the aural side, as it is in Japanese, it becomes all the more powerful. In other words, mystery begets power.

Interestingly, we are seeing a growing divide between writing and pronunciation in our own American names—at least in some groups. We all know how to pronounce John and Sally, but we probably have to pause for a moment before attempting to say Hermione, Nyx, Mia, Kalliope, Xaviera, Enno, J’Kenobia, Shaquita or Travon. Are we turning Japanese—or making an assertion of power?

Have you thought of any other examples that showcase the visual power of names? I’d love to hear about them in the comments.