How do we decide what information can be trusted? There are, of course, innumerable factors that come to play in that decision: the stakes involved, the subject matter, the situation, time constraints…

But if we had to draw out some generalizations when it comes to trusting information, it seems that we inherently trust some kinds of information more than others. Broadly, we can talk about this in terms of formal and informal information. Formal information is information that is organized, structured and traceable by others, and examples include a printed book, an agendaed meeting and a computer database. Informal information, on the other hand, is disorganized, unstrctured and untraceable, and examples include a meandering conversation over coffee, a handwritten memo and smalltalk. If you’re like me, these two categories may immediately strike you as fuzzy; indeed, I think we can best think of formal and informal as poles on a continuum rather than distinct binary categories.

Given this distinction, I’d posit that we inherently trust formal information more than informal information. Broadly speaking, that is. In academia, it’s de rigueur to reference a written source but generally unacceptable to reference a hallway conversation—even if the conversants are established experts. In everyday life, we may not believe what people say unless they can back it up with “sources.” Of course, there are some people we would trust just based on who they are—a loved one, perhaps, or a tour guide—which is an interesting phenomenon to explore further. For now, though, I’ve been thinking about why it is that we—again, broadly and in general—trust formal information more than informal information.

I broached the subject in a recent paper in the Journal of Documentation called “How the Document Got Its Authority.” In that paper, I suggest that human trust is based on persistence (that is, unchangingness), and we trust formal information (that is, documents) because they are persistent.

And the more formal a document is, the more trustworthy it seems to become. For instance, near my apartment in Philadelphia I noticed a “sign” spray-painted in the parking lane that said NO PARKING. People didn’t seem keen to obey, as you can see in the photo to the right. To me, it seems that this is because a spray-painted “No Parking” sign is not as authoritative as the metal, permanent “Yes Parking” sign on the post nearby.

The feature of human cognition that seems to encourage us to trust persistent things more than less-persistent things can make us vulnerable. Not everything permanent is to be trusted. In the article, I give the example of The Onion, a satirical newspaper from my home state (Wisconsin), which was sometimes mistaken as “real” news because of the way it mimicked the newspaper format.

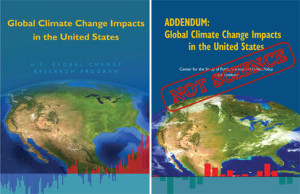

But less innocuously, we can sometimes fall prey to those with pernicious intentions. I recently saw the documentary Merchants of Doubt, for instance, which details how big companies manipulate the public. The film talks about the cigarette industry, for example, and how cigarette companies used manipulative tactics to make the science behind the unhealthiness of smoking seem less clear-cut than it actually was. And the same thing is happening regarding climate change in recent years: Virtually all scientists agree that human-exacerbated climate change is really happening, but a few corporations have managed to put out information that is formal and seemingly authoritative enough to garner respect, making the scientific community seem like it doesn’t have the consensus it does. In the image (source) above and to the right, you can see the legitimate scientific report on the left, and the corporate-sponsored “rejoinder” to the right. The rejoinder features fabricated information that closely mimics the format of the legitimate report.

But less innocuously, we can sometimes fall prey to those with pernicious intentions. I recently saw the documentary Merchants of Doubt, for instance, which details how big companies manipulate the public. The film talks about the cigarette industry, for example, and how cigarette companies used manipulative tactics to make the science behind the unhealthiness of smoking seem less clear-cut than it actually was. And the same thing is happening regarding climate change in recent years: Virtually all scientists agree that human-exacerbated climate change is really happening, but a few corporations have managed to put out information that is formal and seemingly authoritative enough to garner respect, making the scientific community seem like it doesn’t have the consensus it does. In the image (source) above and to the right, you can see the legitimate scientific report on the left, and the corporate-sponsored “rejoinder” to the right. The rejoinder features fabricated information that closely mimics the format of the legitimate report.

In my view, education around what I call document literacy is vital in today’s society. When fake reports and real reports share a common format, how can the average person know what to trust? Those of us who are trained as information professionals are better at this than the average person, and I think it’s our duty to teach our strategies to the public.