Yo, Taylor. I’m really happy for you. Imma let you finish, but Beyoncé had one of the best videos of all time. One of the best videos of all time!

Kanye West, interrupting Taylor Swift’s acceptance speech at the 2009 MTV Video Music Awards

A foundational work in European philosophy is Plato’s Republic. Even today, 2,400 years after it was written, it is still one of the top college texts assigned worldwide. The tome takes the form of a dialogue in which Socrates discusses a number of topics with various interlocutors, from the meaning of justice to the structure of the soul.

An interesting feature of the Republic is the role of interruption in the dialogue. Plato scholar David Roochnik goes so far as to say the Republic is structured around five key interruptions. Perhaps a chief observation here is that the entire book itself is framed as an interruption. The Republic starts this way:

I went down yesterday to the Piraeus with Glaucon the son of Ariston, that I might offer up my prayers to the goddess […] When we had finished our prayers and viewed the spectacle, we turned in the direction of the city; and at that instant Polemarchus the son of Cephalus chanced to catch sight of us from a distance as we were starting on our way home, and told his servant to run and bid us wait for him. The servant took hold of me by the cloak behind, and said: Polemarchus desires you to wait.

Republic, Book I

At this point, the characters go to Polemarchus’ home, where the philosophical dialogue takes place. For Roochnik, the interruptive character of the Republic emphasizes that the book is (a) a conversation, which is how philosophy happens; and (b) deeply human, rather than abstract or systematic in nature.

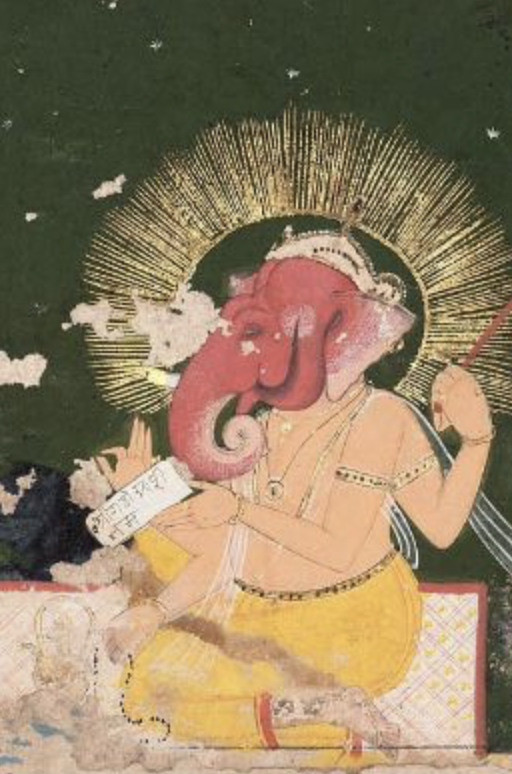

If the Republic is a monument of Western philosophy, the Mahabharata is a monument of Eastern philosophy. It’s a Sanskrit epic—the national epic of India—and one of the major texts of Hinduism. But besides being purely spiritual or historical, the Mahabharata is also deeply philosophical.

I’ve only recently begun studying the Mahabharata, but I’ve already been piqued by the role of interruption in this text as well. Just as with the Republic, the entirety of the Mahabharata is sparked from an interruption: In this case, the seer Vyasa and his disciples have come to interrupt King Janamejaya, who was carrying out a snake sacrifice that threatened to wipe out the entire race of serpents. Nothing like a 1.8-million-word poem about your ancestors to make you forget what you were doing, I suppose.

And just like with the Republic, the dialogue of the Mahabharata is dotted with interruptions along the way. Perhaps the most famous is when Prince Arjuna is riding into war alongside his charioteer Krishna, when he calls Krishna to pause in no man’s land—”time freezes,” says my translation—to have a discussion about metaphysics and ethics. In the West, this part of the Mahabharata is best known of all: It’s the Bhagavad Gita.

I’m not sure what to make of all this yet. Perhaps it is only that we humans interrupt each other, and that interruption is present in any dialogue. But it seems that there’s something deeper at play.

In the Republic, Plato makes the point that learning is a matter of turning around—exemplified in the Allegory of the Cave—of questioning, of thinking, of dialogue. Perhaps these are all forms of interruption. This is quite interesting, given that the word interruption has a negative connotation: we don’t want to be interrupted, and we feel we shouldn’t interrupt other people. Then again, we don’t quite like learning, either, and we avoid it when we can. But when is interruption good, and when is it Kanye West at the 2009 VMA’s? (Or is it, perhaps, that Kanye West was being the consummate philosopher here?)