In my work as a college essay writing tutor, I’ve noticed that a lot of people have trouble using punctuation. Now, many people seem to believe that trouble with punctuation stems from a failure to memorize and implement a bunch of usage rules, but I’ve come to a different conclusion: If you’re struggling with punctuation, you simply haven’t yet fully thought through your argument.

Let’s begin by clarifying what I mean by punctuation. Punctuation, as I understand it, is anything that stops a piece of writing from being just a string of letters. Punctuation is what helps us define the boundaries between words and even larger segments. Consider these two examples:

- No punctuation: Heycanyoupackmyboxwithfivedozenliquorjugs

- Punctuation: Hey, can you pack my box with five dozen “liquor” jugs?

We have quite a few different punctuation marks at our disposal. Let’s consider a number of them:

| Space | Line Break | Period | Comma | Exclamation Mark | Question Mark |

| x x | x x |

x. | x, | x! | x? |

| Colon | Semicolon | Hyphen | Dash | Quotation Marks | Parentheses |

| x: | x; | x–x | x—x | “x” | (x) |

We use each of these under certain circumstances. We can seek to understand the usage of each one in terms of a series of rules typically learned in school, or we can think about them in terms of the meaning they contribute to a piece of writing. I believe the latter is much more effective. More specifically, the meaning that punctuation contributes is a description of how the elements—the words, phrases, clauses, sentences and paragraphs—relate to each other. In other words, punctuation reveals the organizational structure of writing. Failure to implement them correctly indicates, to me, not a failure to memorize rules, but a failure to analyze sufficiently. When it comes down to it, writing is a symbolic, systematic way to convey thought. Writing is organized, and one of the ways we organize our writing is through the use of punctuation.

Let’s briefly consider the meaning each of the punctuation marks I’ve mentioned above contributes:

- Space – Separates words.

- Line Break – Separates paragraphs, which are conceptual units. A new paragraph signals a change in topic.

- Period – Separates sentences. (Also used to indicate abbreviations.)

- Comma – Separates phrases, often for clarity.

- Exclamation Mark – Lends a tone of surprise or excitement to the preceding sentence.

- Question Mark – Lends a tone of question or wonderment to the preceding sentence.

- Colon – Indicates that the following words stem directly from the preceding phrase.

- Semicolon – Indicates that the preceding sentence and the following sentence are closely linked.

- Hyphen – Unites two words.

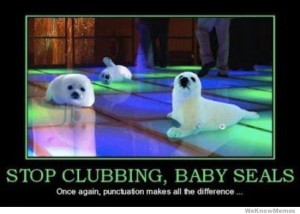

- Dash – Indicates a sudden change. Used as a pair to inject a thought amidst an ongoing stream, or in the singular to tack on an unrelated thought to the beginning or end of a sentence.

- Quotation Marks – Indicate speech. May also indicate that a word is not to be interpreted as usual (either to suggest a novel usage of the word or to call attention to the word itself).

- Parentheses – Indicate superfluous information.

If you have trouble with punctuation and you find yourself wondering if you really need a comma there or if such and such is an appropriate place for a paragraph break, instead of googling for a list of rules, sit back and think about how the chunks of your writing relate to each other. One punctuation mark I bet you’ve mastered is the space; we use spaces to indicate that the things around each space are to be understood as separate words. This seems quite obvious and natural to us. But perhaps you haven’t considered the intuitive possibility of omitting a space to indicate that two “words” should be considered a single entity.

When we get into suprasegmental distinctions, punctuation gets a bit trickier. But don’t lose heart. Ask yourself questions like:

- Does this part function as a complete thought on its own, or does it rely on something else I’ve written (either before or after) to be understood?

- How does it relate to what precedes and follows it?

- Am I starting a new topic here?

You may find it difficult at first. Certainly, any new skill is difficult at first, and a change in mindset can make a task seem more difficult still. All in all, I think this way of thinking about punctuation is more beneficial than expecting you to wrap your head around dozens of rules, which frankly come along with dozens of exceptions anyway. When it comes to writing, we shouldn’t be slaves to detached rules; instead, we should understand how punctuation affects interpretation, and use it to more precisely convey our thoughts.

To drive this point home, let’s consider the following nonsense utterance:

Lorem, ipsum dolor sit amet (consectetur adipiscing elit) ut—eleifend ultrices—vulputate, “Interdum et malesuada fames ac ante ipsum primis in faucibus?”

We don’t know what this means, but to say that we get absolutely no information from it isn’t exactly true. Indeed, we can surmise some things…. We know that “lorem,” “ipsum” and “dolor” are all separate words. We know that “lorem” here is some sort of introductory thought—probably an adverb. We know that “consectetur adipiscing elit” is some nonessential information, and we know that “Interdum et malesuada fames ac ante ipsum primis in faucibus” is a spoken utterance that is also a question. So, while we can’t fully understand what’s written, we can begin to understand some of the grammar—in other words, how the written elements relate to each other.