I’ve been hard at work on my dissertation proposal—I’m studying the processes of artistic self-portraiture—and I’ve been thinking about self-documentation. In modern society we seem to be compelled to write about ourselves. We make resumes and CVs, and we write bios for our social media profiles, which are becoming central for everything from everyday communication to dating and business. There are, of course, also many non-verbal ways in which we document ourselves, which is a focus of my dissertation.

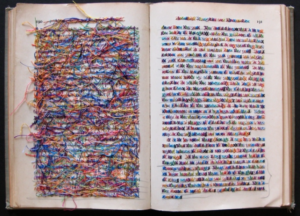

The later work of Michel Foucault suggests that self-documentation is not new. On the contrary, many in Ancient Greece and Rome apparently kept hupomnēmata, or notebooks “to collect what one has managed to hear or read, and for a purpose that is nothing less than the shaping of the self.” These were fragmentary notebooks, but their result was not merely a collection of disjointed scraps; rather, they contributed to a new whole, along with the writer themselves. According to Foucault, the purpose of the hupomnēmata was to care for the self, which was an ancient directive. (Foucault laments that today we only recall know thyself, having forgotten about care for thyself.) As Foucault writes, “writing transforms the things seen or heard ‘into tissue and blood.’” People regularly returned to their hupomnēmata for nourishment.

The function of the hupomnēmata is quite different from the modern genre of autobiography, whose purpose is not to care for the self but to care for others. Autobiographies and many other self-documents are packaged for sale (in various senses), but the hupomnēmata were intensely private. They were more about the process than the product.

Today, some of us keep hupomnēmata. Mine, if you could call it that, is in Evernote. But I think this is a rare practice. On the other hand, many people cultivate something like hupomnēmata in their social media feeds. A Twitter feed, for instance, presents a seemingly disjointed collection of thoughts and snippets from the world, and it seems to be both like and unlike hupomnēmata. On Twitter (and other social media, or even ICT-made self-documents in general), are posts revisited as a means of self-care? Is the primary audience the self or another?

Lately I’ve been reading

Lately I’ve been reading