I wrote before about the exhibition on historical books in India currently on view at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. If you’re in the area in the near future, it’s worth a look! There’s another interesting tidbit from this exhibition that I’d like to share.

I’ve considered before questions related to text directionality. Basically, what is it that determines how we write? We have text written upwards spiraling in fanciful directions, such as on the ancient Ogham monuments in Ireland. We have vertical texts and we have horizontal texts. And then we can consider all the supports writing has seen over the years: stone, turtle shells, clay, wood, leaves, paper, metal, skin, pixels… all of which have limitations with respect to size and shape. Did these limitations contribute to text directionality in the early days of human writing? Who knows.

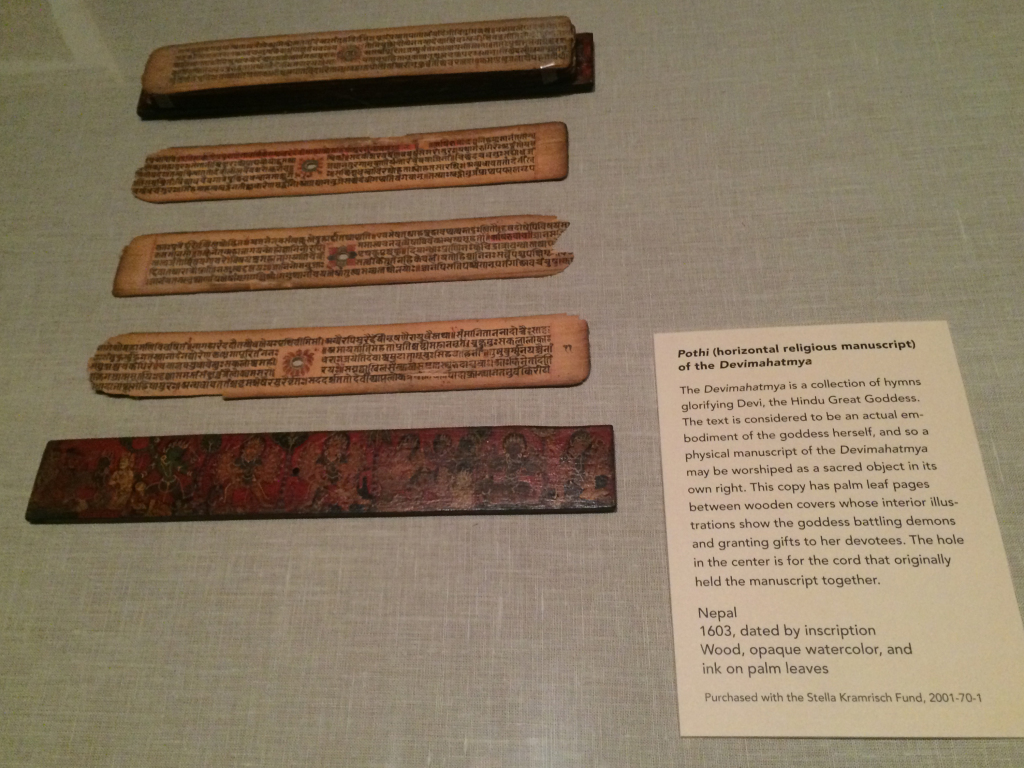

One thing we can be sure of is that the support played a large role in how pages were designed. Above we see pages made from palm leaves. Of course, palm leaves are long and narrow, so the pages had to be designed such that they could be read in this format.

There are samples of similar texts elsewhere in the exhibit, with an interest twist-slash-historical-development. As the signage explains:

The earliest Jain manuscripts were made from palm leaves. Since the size of the leaf could not be changed, the text and images were designed to fit its surface. In these pages, a few lines of writing run from the left to the right margin. Images occasionally punctuate the text, each encapsulating an important episode. The hole in the middle of the page was for the string that once tied the pages together and secured their wooden covers. To read a book, a person would loosen the string and flip the pages vertically.

When paper replaced palm leaf in the 1300s, artists could change the dimensions of the page to accommodate more text and larger images. However, the long horizontal format was sanctified by religious tradition and continued to be used. Likewise, even though paper manuscripts were no longer tied together with string, artists regularly placed a red circle in the middle of each page to imitate the hole from the palm leaf tradition.

This, I suppose, is another example of skeumorphism, which I’ve discussed before. Now, religious sanctity is one thing, but taking advantages of the non-limitations when changing support is an important opportunity. So let’s consider: What are we missing out on when we model e-books after physical books?

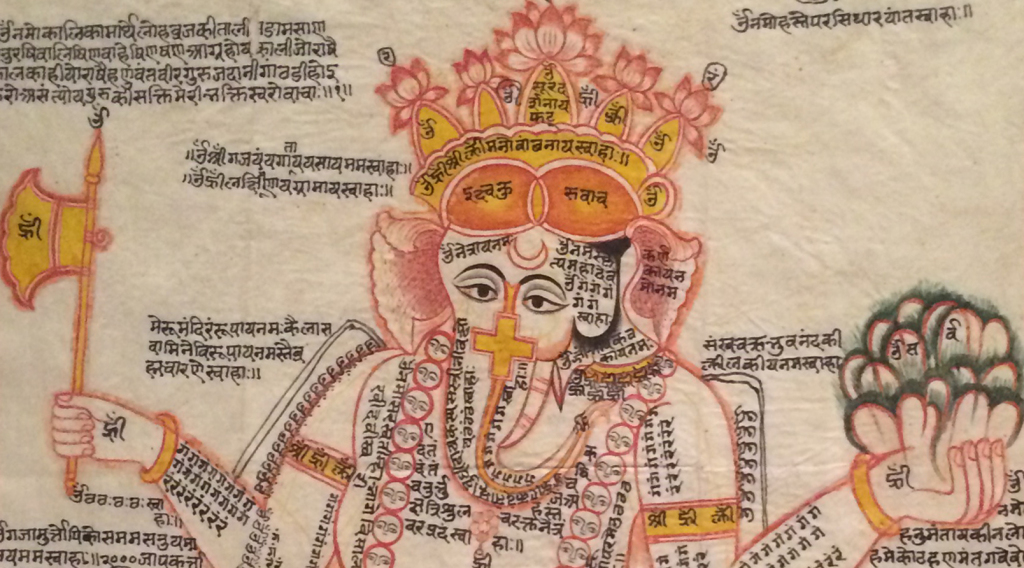

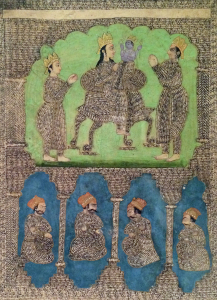

The image to the right (18th century), for example, presents the newborn Krishna as the god Vishnu. At first it seems that it’s a simple drawing, but upon closer inspection we see that the shading is actually comprised of endless repetitions of भगवान् (Bhagavān), the Hindu theonym referring to Vishnu/Krishna. In this sense, it labels the information—but it’s so much more than that. As the museum plaque informs, “The repeated writing of the god’s name not only turns the illustration of a holy subject into an icon for devotion, but also serves as an act of devotion in itself.” Thus we can appreciate this page not only as a finished piece—as we see it here—but also as a process, something that was experienced by the person who made it.

The image to the right (18th century), for example, presents the newborn Krishna as the god Vishnu. At first it seems that it’s a simple drawing, but upon closer inspection we see that the shading is actually comprised of endless repetitions of भगवान् (Bhagavān), the Hindu theonym referring to Vishnu/Krishna. In this sense, it labels the information—but it’s so much more than that. As the museum plaque informs, “The repeated writing of the god’s name not only turns the illustration of a holy subject into an icon for devotion, but also serves as an act of devotion in itself.” Thus we can appreciate this page not only as a finished piece—as we see it here—but also as a process, something that was experienced by the person who made it.