I recently read the extraordinary book Mastery, by Robert Greene. (As an aside, if Outliers left you a bit dejected, you’ll want to check out this book.) I was inspired by the story of Jean-François Champollion, who was the first to crack the Egyptian hieroglyphic text on the Rosetta Stone. Champollion’s interests in Egyptology and Coptic—and his novel approach to decipherment, beginning with the proper names and extrapolating outward—equipped him to unlock the script of the pharaohs; I looked into my life experience and wondered what sort of path I might be setting myself up for…

Not a day later, my brother told me about the Voynich manuscript, a 15th-century codex in an unidentified language that is often called “the most mysterious document in the world.” As a recent article in the Boston Globe describes,

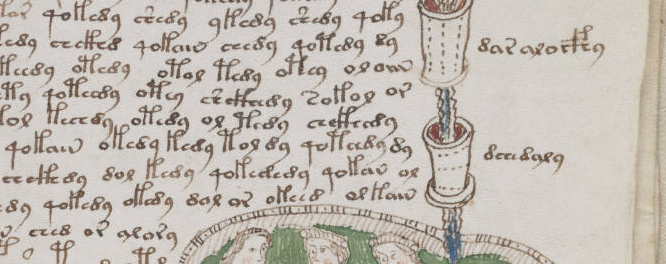

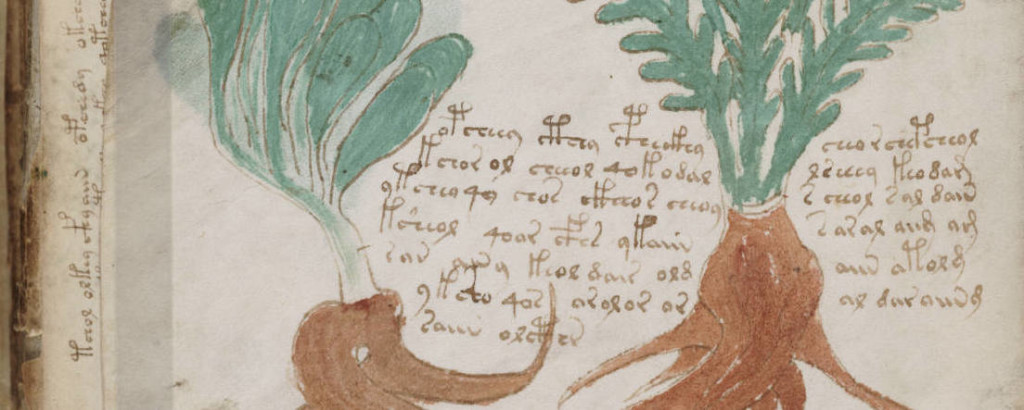

Here is what is known about the Voynich manuscript: It consists of 246 pages of handwritten script and illustrations. It was discovered in an Italian monastery by a Lithuanian bookseller named Wilfrid Voynich in 1912.

Here is what is not known: Just about everything else. The greatest code breakers of the last 100 years have failed to decipher the Voynich manuscript’s ornate script, or even agree on whether it says anything at all. Experts have theorized that it was written in Europe, Asia, or South America; they have speculated that it was created by Leonardo da Vinci, by 13th-century philosopher Roger Bacon, or Wilfrid Voynich himself. When it comes to code breaking, “The Voynich is the Mount Everest of the genre and the K2 at the same time,” said Nick Pelling, a British computer programmer.

Immediately, of course, I fantasized about myself being the one to decipher it. My love of all things Basque led me to the conclusion that it might have been written in Euskara (which was not mentioned as an already-identified possibility on the Wikipedia article), and I leapt to work, taking Champollion’s lead by looking for anything I might be able to unequivocally identify as a proper noun so as to serve as a starting point. (Champollion was greatly aided by the fact that the pharaohs’ names were inscribed in cartouches on the Rosetta Stone, making them stand out.) I was at it for hours, going through every page of the Voynich manuscript, when I turned to the Internet to learn more about what was already understood about it (beyond what the Wikipedia page had already told me).

Online I learned that Stephen Bax has already been at this task for quite some time, and I suspect his knowledge of several Middle Eastern languages may be for him what knowledge of Coptic was for Champollion. Bax has taken a novel approach (much in the way of Champollion) by looking at the manuscript starting with the letters themselves, rather than using the type of big data analysis that has been popular with the cryptographers on the job. And, after uncountable hours, he’s identified a star and a number of herbs, associating a handful of characters with their sound values, and I believe he’s well on his way.

Perhaps more interestingly, Bax keeps track of his progress and musings on his website, where he welcomes comments, insights and discoveries from readers. This way, instead of locking himself in the ivory tower, jealously trying to decode the manuscript alone so that he’ll lay claim to all the credit, he invites the world at large to take part in the work. I’m sure this will, in the end, lead to a quicker solution. Such crowdsourcing will help, for example, identify the obscure plants that grace the pages of the manuscript, which Bax could certainly not do alone. (And, of course, it’s a thoroughly 21st-century approach.)

Follow

Follow

Actually, Bax’s approach to the Voynich Manuscript is one that has been employed many times already, without any success at all beyond a few partial, somewhat unsatisfactory words. Which, perhaps not coincidentally, is as far as he has got as well.

And as far as ‘crowdsourcing’ research goes, this has been going on in the Voynich world since at least 1990, so Bax is riding a wave that has long been rolling.

Maybe it is some form of Basque: but the smart money (since about 1950) has been on a cipher. Just so you know. 🙂

I can’t help but keep thinking of Champollion; in his day, there were plenty of folks (favored to be the ones to crack the code) who were approaching the problem as a cryptographic one, with no success. Could there be a parallel here?

Of course, I’m more of a spectator than a participant in this… so I’m just enjoying the show for now :).

I guess you could look at academia in general as a form of crowdsourcing, now that I think of it, but I thought Bax’s blog format was especially cool, since it opens it up to laypeople who might have expertise in obscure corners. I wasn’t aware it was going on elsewhere, though! (I am, after all, just getting into the Voynich research.) Do you have any links you could share? I’d be interested.

Just saw this – thanks for your kind words.

It’s sad to see Nick Pelling trying to dampen your enthusiasm. I agree with you that the way forward is to be open to different opinions and consider each one carefully. We get nowhere if we stick rigidly to one view and try to attack all others.

BTW, if I were rude I might ask how many words Nick has managed to decode in several decades of trying. Luckily I’m not rude enough to ask 🙂

And as for Basque? Not impossible!