I’m currently reading the book The Singularity Is Near: When Humans Transcend Biology, by Ray Kurzweil. The author predicts the not-so-far-away union of human and machine. It’s kind of a terrifying read. (What does that say about me?)

Anyway, there’s a section in the book where he discusses the life cycle of technology, which has seven stages:

- Precursor. Prerequisites for a technology exist, but have not yet been put together.

- Invention.

- Development. The invention is protected and supported. Kurzweil cites the many “tinkerers” who invented horseless carriages, but the development ingenuity of Henry Ford who helped the automobile really take root.

- Maturity. The continues to evolve, but it’s been well adopted by the community. It may seem so indispensable that a lot of people think it will last forever.

- Threat. An upstart threatens to eclipse the older technology. This upstart may have some unique benefits, but overall it is found to be lacking, and finally it is rejected. The people from the previous stage take this as further proof that the technology in question will live forever.

- Successor. Another new technology comes along that is significantly better than the threatening upstarts. The technology in question gradually declines and obsolesces.

- Antiquity. The technology finally fades out. Kurzweil cites the horse and buggy, the harpsichord, the vinyl record and the manual typewriter as examples of such bygone tech.

Kurzweil goes on to spotlight the printed book, predicting that it, too, will fade away. The book was written in 2005, when e-reader tech was only beginning to bud, but already he saw the writing on the wall. And sure, there are plenty of people who don’t touch books. Even for bibliophiles like myself, most of the reading we do is in electronic form.

But taking that as evidence that books are obsolete assumes that the content is all that matters. And so hey but wait—look at those examples in Stage 7. I see horse-and-buggies prancing around the city from time to time. I have friends who still swear by vinyl. I have at least one friend who is a regular user of a manual typewriter. Yes, these things are obsolete in the popular sense of the term, but that doesn’t mean they don’t have any uses.

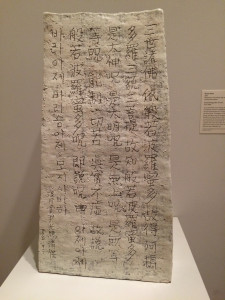

At the Philadelphia Museum of Art I recently saw a wonderful sculpture, pictured to the right, by South Korean ceramic artist Yoon Kwang-cho. Here the artist has carved the Buddhist Heart Sutra onto a clay slab. But wait, aren’t clay inscriptions obsolete? Of course, since this is an objet d’art, we can surmise that there’s more to the story. It’s what the medium symbolizes—its place in culture. It’s the tactile experience of creating art. It’s the act of creating rather than selecting characters from a font made by someone else.

At the Philadelphia Museum of Art I recently saw a wonderful sculpture, pictured to the right, by South Korean ceramic artist Yoon Kwang-cho. Here the artist has carved the Buddhist Heart Sutra onto a clay slab. But wait, aren’t clay inscriptions obsolete? Of course, since this is an objet d’art, we can surmise that there’s more to the story. It’s what the medium symbolizes—its place in culture. It’s the tactile experience of creating art. It’s the act of creating rather than selecting characters from a font made by someone else.

Different technologies have different affordances. And even after they go “obsolete,” we can still find value in those affordances.

Kurzweil predicts the downfall of the printed book because e-reader technology has improved so that (1) it no longer hurts your eyes, (2) resolution has increased, (3) the devices are about the size of or even smaller than print books, (4) these devices are more feature-laden, (5) they hold more content, (6) that content is more easily navigable, and (7) battery is becoming a non-issue. He says the biggest limiting factor is going to be a distribution model that satisfies publishers. Remember, this book is from 2005. I think we’ve achieved that model. (Keep in mind I am not in the publishing world, so they might have something to say…)

But anyway, I don’t think books are going anywhere. And it’s precisely because they are single-purpose devices. Reading a book is contemplative, because Facebook isn’t a click away. No notifications are coming in. It’s tactile. And physicality is important, since we’re physical creatures. In our world of multi-purpose this and that and multitasking madness, books are refreshing precisely because they only do one thing. I’m currently conducting a study on how people read the Bible, and many of these findings are surfacing (full findings coming later this year).

Maybe I’m one of those clingers in Stage 4 and 5 of the life cycle described above. But I’m not alone. David Bawden, editor of the Journal of Documentation, pointed out in the introduction to the journal’s latest issue that we’re experiencing a general trend toward “slow” information, as evidenced by, for example, the proliferation of super-simple computer interfaces and websites.

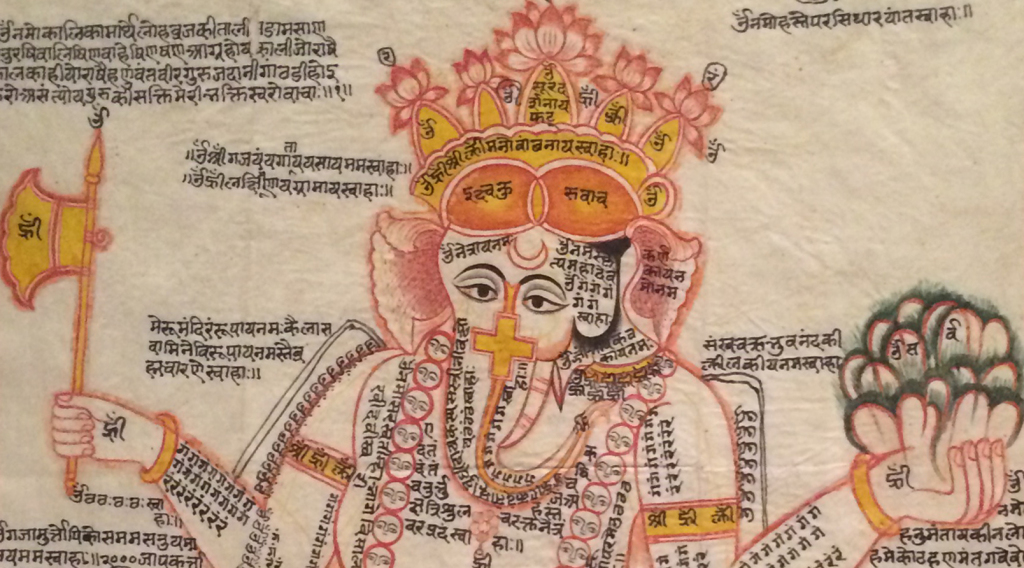

The image to the right (18th century), for example, presents the newborn Krishna as the god Vishnu. At first it seems that it’s a simple drawing, but upon closer inspection we see that the shading is actually comprised of endless repetitions of भगवान् (Bhagavān), the Hindu theonym referring to Vishnu/Krishna. In this sense, it labels the information—but it’s so much more than that. As the museum plaque informs, “The repeated writing of the god’s name not only turns the illustration of a holy subject into an icon for devotion, but also serves as an act of devotion in itself.” Thus we can appreciate this page not only as a finished piece—as we see it here—but also as a process, something that was experienced by the person who made it.

The image to the right (18th century), for example, presents the newborn Krishna as the god Vishnu. At first it seems that it’s a simple drawing, but upon closer inspection we see that the shading is actually comprised of endless repetitions of भगवान् (Bhagavān), the Hindu theonym referring to Vishnu/Krishna. In this sense, it labels the information—but it’s so much more than that. As the museum plaque informs, “The repeated writing of the god’s name not only turns the illustration of a holy subject into an icon for devotion, but also serves as an act of devotion in itself.” Thus we can appreciate this page not only as a finished piece—as we see it here—but also as a process, something that was experienced by the person who made it.