This year we’ve been confined to home much more than usual. This has prompted a lot of thinking, mostly about what I can’t do. I like my apartment, but it can be small and lonesome at times, particularly eight months into a pandemic. But lately I’ve been exploring what being at home enables, rather than what it precludes.

What if our home was not just the place we live (or worse, just the place we’re stuck) but a space of inspiration? In Care of the Soul, psychotherapist Thomas Moore writes of the possibility for considering the home as a sort of modest museum—and museums are, in the end, all about inspiration. We can furnish our home with well-loved items and decorate it with objects of personal meaning. Furniture and art, sure, but also special rocks, leaves and branches.

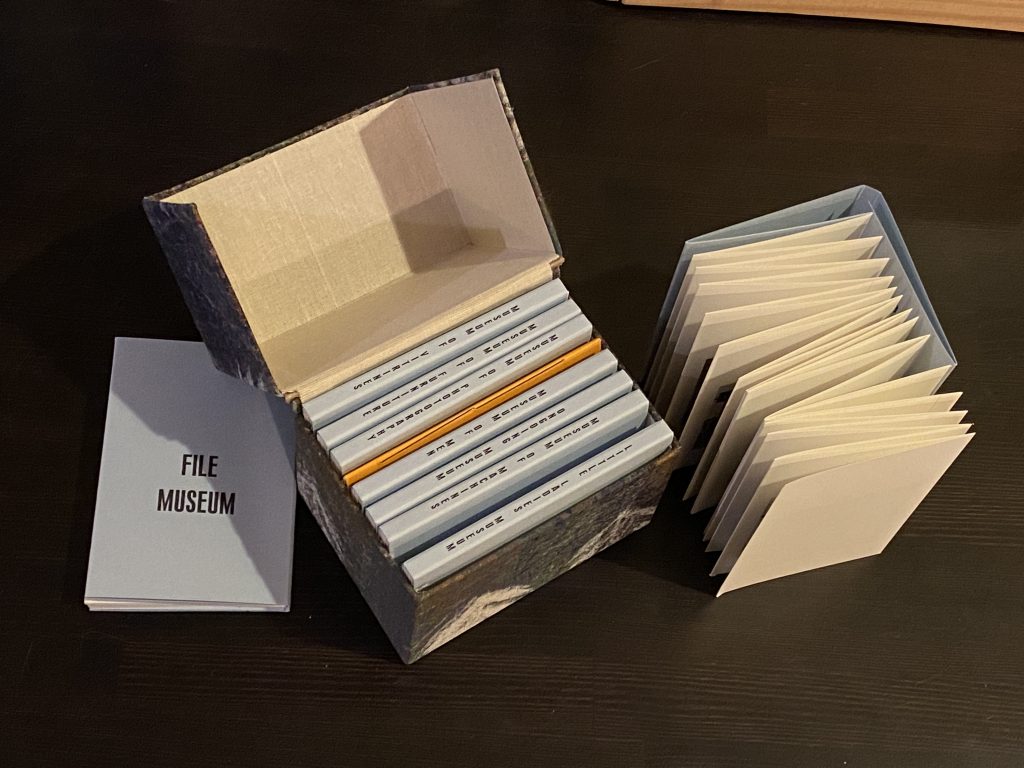

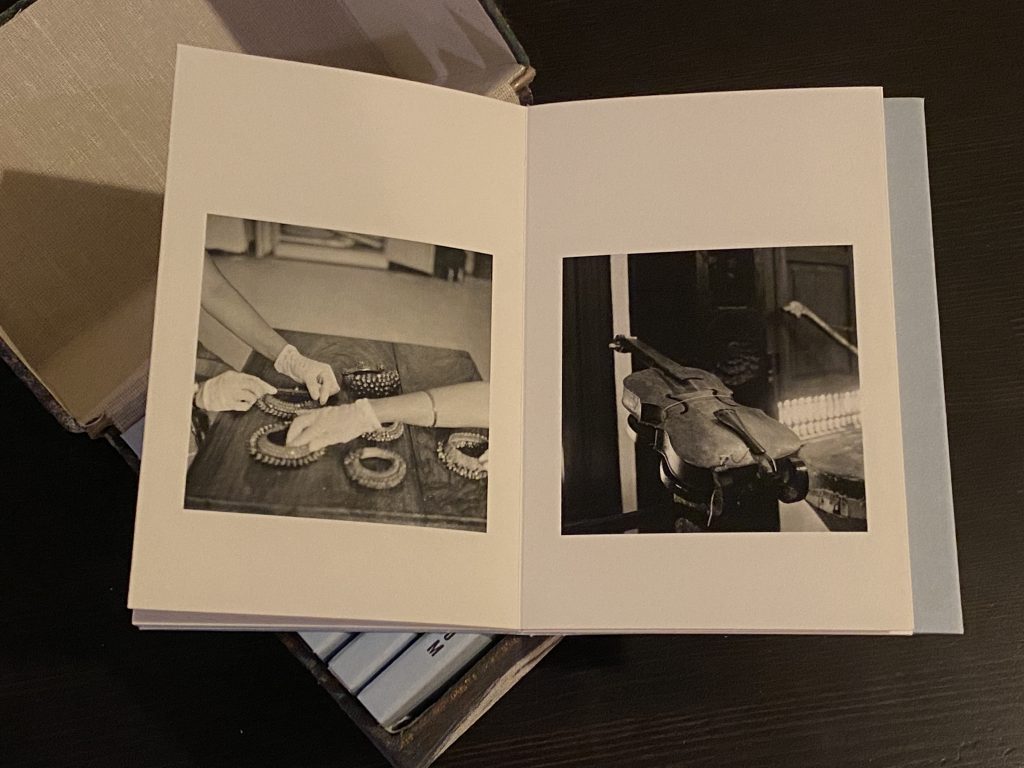

I have a lot of art in my small apartment, but one interesting piece that this train of thought reminds me of is my Museum Bhavan—which is at once a book, a museum and a work of art. Created by Dayanita Singh, the bhavan contains nine museums, small accordion booklets of photographs with titles like “Museum of Furniture” and “Museum of Vitrines.” These museums can be set out on a table for display or paged through in handy exploration. Museum Bhavan enchantingly blurs the boundary between book, art and space.

From reading Moore, I learned about the medieval concept of liber mundi, or “book of the world.” It refers first to our belief that the world is comprehensible and can be learned about in the same way that texts are comprehensible and can be learned about. Scientists, for instance, read the world as liber mundi in this way. More deeply, the term also refers to a sort of what we might call spiritual literacy, a capacity to encounter the mysterious and sacred in our environs.

This concept traces back to the Gospel of John, which begins, “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God… and the Word became flesh” (John 1:1–14), suggesting that the world is at once material (flesh), rational (Word), and divine (God). In our modern eagerness to dispense with tales of a bearded man in the clouds, we seem to have also done away with our capacity to experience the world as a deep mystery—a question to be lived, and not just answered. Maybe the spiritual literacy of liber mundi is just what we need here.

What I am suggesting is there is not a clean line of separation between reading a book and reading the world; after all, books are part of the world. Like Borges I cannot sleep unless I am surrounded by books. But maybe that is the case for us all.

Follow

Follow