As I talked about in an earlier post, the Latin alphabet is now used to represent more languages than any other script system. But the Latin alphabet doesn’t have a character for every sound in the world; it was created to represent Latin, and it’s been adapted somewhat since then, but there are still plenty of natural language sounds out there that have no corresponding Latin character. In order to represent these sounds in the Latin alphabet without creating a new letter—an expensive proposition—we’ve relied on diacritical marks, as seen in ù, ú, û, ũ, ū, ŭ, ü, ủ, ů, ű, ǔ, ȕ, ȗ, ư, ụ, ṳ, ų, ṷ, ṵ, ṹ, ṻ, ǖ, ǜ, ǘ, ǖ, ǚ, ừ, ứ, ữ, ử, ự, and ʉ, as well as combinations of letters, such as ch.

But sometimes diacritics and multigraphs aren’t used to represent new sounds. Sometimes they’re used for ideological reasons, to create the illusion that a language is more unique than it actually may be. For example, when planning the Basque orthography, the language moguls decided to use tx to represent the same sound that ch represents in Spanish. Why create a new digraph when an existing one would serve perfectly well? One reason, surely, is because the invented digraph would emphasize that Basque is not Spanish—that the Basques are not Spanish!

There’s an interesting result of all this: Because of the unique characters and character combinations of many languages, it’s fairly easy to tell what language something is written in, even if you don’t know that language. If you see an ü and a sch in some text, it’s probably German, and if there was a ß, that’d give it away for sure.

I hypothesized that this would even work with made-up words.

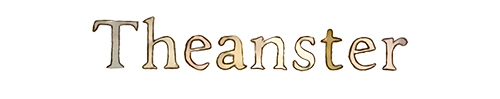

This idea was the basis for an art project of mine, in which I considered the most defining characteristics of several languages: average number of letters per word, most common beginning and ending letters, most frequent letters, and unique or stereotypical multigraphs, characters or punctuation marks. As a result, I’ve created, among others, the most English fake English word.

The resulting words are interesting enough, but instead of simply printing them here like any other text, I traced their typeset forms and filled them in with watercolor, arousing meditations on mechanical reproduction, handwriting and creation.

See if you can tell which languages the rest of these made-up words are written in.

Follow

Follow